By Alexander F. Magee

The internet has long been championed as a marketplace of ideas that fosters unprecedented access to different viewpoints and mass amounts of information and media. At least in the eyes of some, Section 230 of the Communications Decency Act (“CDA”)[1] is largely responsible for the internet gaining that reputation, and the Section has therefore become something of a beacon for free speech.[2] In recent years, however, the Section has received considerable negative attention from both sides of the political spectrum, including explicit denouncement from both President Donald Trump and the Democratic Presidential Nominee Joe Biden.[3] What started as dissatisfied grumblings about unfair censorship orchestrated by tech companies, culminated in President Trump enacting an Executive Order in May calling for changes in the Section that would create greater liability for companies such as Facebook, Twitter, and Google.[4]

The CDA was first enacted in 1996 as an attempt to prevent children from accessing indecent material on the internet.[5] The Act made it a crime to knowingly send obscene material to minors or publish the material in a way that facilitates it being seen by minors.[6] Section 230 was conceived in-part as a way to facilitate this prevention goal, by allowing websites to “self-regulate themselves” by removing indecent material at their discretion.[7] While certain parts of the Act were quickly declared unconstitutional in the Supreme Court decision Reno v. American Civil Liberties Union,[8] Section 230 survived to become arguably the most important law in the growth of the internet.

The relevant language in the Section itself is contained in a “Good Samaritan” provision that states: “No provider or user of an interactive computer service shall be treated as the publisher or speaker of any information provided by another information content provider,” and that the provider shall not “be held liable on account of any action . . . taken in good faith to restrict access to or availability of material that the provider . . . considers to be obscene, lewd, lascivious . . . or otherwise objectionable, whether or not such material is constitutionally protected.”[9] This means Twitter, or a similar site, cannot be held liable for the objectionable material a third-party posts on their platform, subject to limited exceptions.[10] It also means that any action taken by Twitter to remove content they deem to be offensive or objectionable is protected as a way to encourage sites to remove offensive content by allowing them to do so without concern of liability.[11]

President Trump apparently takes issue with this “Good Samaritan” protection. In his May Executive Order, President Trump called social media’s moderation behavior “fundamentally un-American and anti-democratic,” and specifically accused Twitter of flagging and removing user content in a way that “clearly reflects political bias.”[12] President Trump also accused unspecified U.S. companies of “profiting from and promoting the aggression and disinformation spread by foreign governments like China.”[13] To address these concerns, the Executive Order calls for a narrowing of Section 230 protections, making it so that social media companies can be held liable for what their users post or for moderating those posts in a way that is “unfair and deceptive.”[14] Four months later, the Department of Justice proposed legislation aimed at weakening Section 230 protections.[15] The legislation is drafted in the spirit of the Executive Order, with special emphasis being paid to holding platforms accountable for hosting “egregious” and “criminal” content, while retaining immunity for defamation.[16]

Presidential Nominee Biden, for his part, seems to be more focused on holding tech companies liable for misinformation that is spread on their websites. In a January interview, Biden stated that tech companies should be liable for “propagating falsehoods they know to be false.”[17] Biden took particular umbrage with Facebook’s hosting of political ads that accused Biden of “blackmailing” the Ukrainian government, and he further stated that Mark Zuckerberg should be subject to civil liability for allowing such behavior.[18]

For a law that has garnered so much recent controversy, and one the public has taken for granted until relatively recently, it’s worth considering what the implications of removing Section 230 protections would be. Internet advocacy groups have vehemently criticized any Section 230 amendment proposals, and have generally painted a bleak picture of the ramifications of such changes.[19] These groups’ prognostications of the legal landscape without Section 230 protections generally predict social media sites will be facing a legal quagmire. Theoretically, sites would not only be exposed to liability for taking down certain third-party content, but also for not taking down other third-party material, which would effectively create a minefield of liability.[20] Internet Association, a trade association that represents preeminent tech companies such as Amazon, Facebook, and Google, has repeatedly attacked any threat to amend Section 230 as detrimental to the internet economy, and recently invoked the First Amendment as reason enough for social media companies to be able to “set and enforce rules for acceptable content on their services.”[21]

The latest serious threat to Section 230 has come from the FCC. On October 15, FCC Chairman Ajit Pai expressed his intention to move forward with a rulemaking request, stating that, while social media companies have a right to free speech, they do not have a “First Amendment right to special immunity denied to other outlets, such as newspapers and broadcasters.”[22] Several Democrats have challenged the FCC’s motives and overall authority to amend the Section.[23] The FCC, in response, asserts a fairly simple argument. The idea is that their authority rests in the language of the Communications Act of 1934, which in Section 201(b), gives the FCC explicit rulemaking power to carry out provisions of that Act.[24] In 1996, Congress added Section 230 to this Communications Act, therefore giving the FCC power to resolve any ambiguities in Section 230.[25] According to the FCC, two Supreme Court cases, AT&T v. Iowa Utilities Board[26] and City of Arlington v. FCC,[27] uphold their power to amend Section 230 pursuant to Section 201(b).[28]

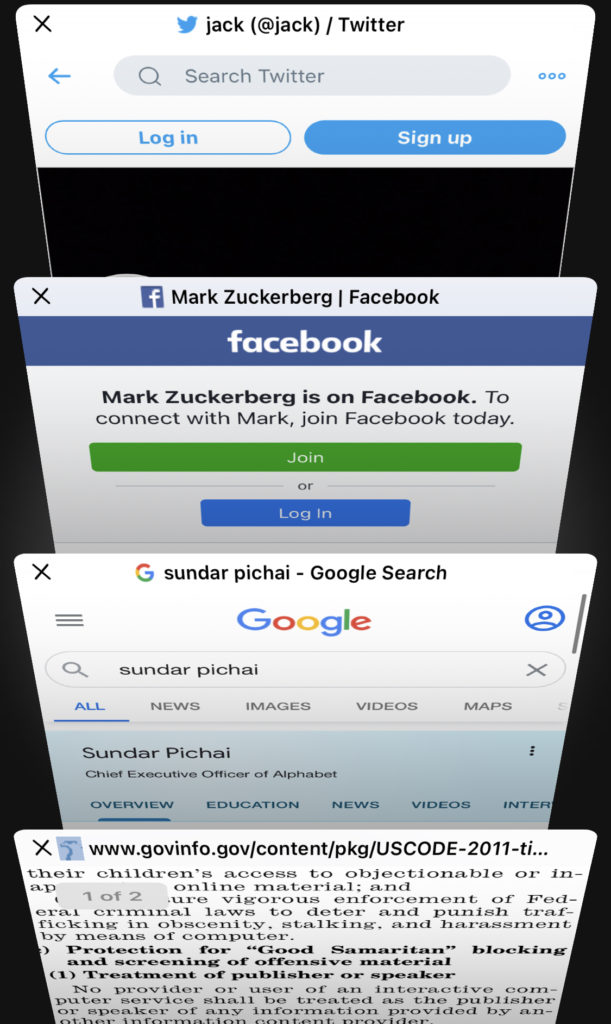

The FCC’s push towards rulemaking came quickly after conservative-led criticisms of Section 230 reached a fever pitch following the circulation of a New York Post story containing potentially damaging pictures and information about Joe Biden’s son Hunter Biden.[29] Twitter and Facebook removed posts linking the story, on the basis that it contained hacked and private information.[30] The two sites have continuously denied suppressing conservative views[31] but, regardless, the Senate Judiciary Committee voted 12-0 to issue subpoenas to Jack Dorsey and Mark Zuckerberg, the sites’ respective CEOs, regarding their content moderation.[32] In anticipation of their hearings, Dorsey and Zuckerberg continued to passionately defend the Section, while Dorsey committed to making moderation changes at Twitter and Zuckerberg advocated for greater governmental regulation of tech companies in general.[33] Alphabet CEO Sundar Pichai, another tech leader subpoenaed, called Section 230 “foundational.”[34] The hearing took place on Wednesday and, according to early reports, was grueling.[35]

Lastly, on October 13, social media companies started to feel pressure from the Supreme Court. Justice Clarence Thomas voiced his concerns with the Section, stating that “extending §230 immunity beyond the natural reading of the text can have serious consequences,” and it would “behoove” the court to take up the issue in the future.[36] In the face of an impending election, uncertainties abound. However, one thing seems undeniable: Section 230 has never felt more heat that it does right now.

[1] 47 U.S.C § 230.

[2] See Section 230 of the Communications Decency Act, Elec. Frontier Found., https://www.eff.org/issues/cda230 (declaring Section 230 to be “The Most Important Law Protecting Internet Speech”).

[3] Cristiano Lima, Trump, Biden Both Want to Repeal Tech Legal Protections- For Opposite Reasons, Politico (May 29, 2020), https://www.politico.com/news/2020/05/29/trump-biden-tech-legal-protections-289306.

[4] Exec. Order No. 13,925, 85 Fed. Reg. 34,079 (May 28, 2020).

[5] See Robert Cannon, The Legislative History of Senator Exon’s Communications Decency Act, 49 Fed. Comm. L.J. 51, 57 (1996).

[6] See id. at 58.

[7] 141 Cong. Rec. H8,470 (daily ed. Aug. 4, 1995) (statement of Rep. Joe Barton), https://www.congress.gov/104/crec/1995/08/04/CREC-1995-08-04-pt1-PgH8460.pdf.

[8] 521 U.S. 844 (1997).

[9] 47 U.S.C. § 230(c)(1)–(2)(A).

[10] For instance, the protection is not available as a defense to sex trafficking offenses. 47 U.S.C. § 230(e)(5).

[11] See Content Moderation: Section 230 of the Communications Decency Act, Internet Assoc., https://internetassociation.org/positions/content-moderation/section-230-communications-decency-act/ (last visited Oct. 24, 2020) (providing explanation of “Good Samaritan” provision).

[12] Exec. Order 13,925, 85 Fed. Reg. at 34,079.

[13] Id.

[14] Id. at 34,081–82.

[15] The Justice Department Unveils Proposed Section 230 Legislation, Dep’t of Just., (Sept. 23, 2020), https://www.justice.gov/opa/pr/justice-department-unveils-proposed-section-230-legislation.

[16] Department of Justice’s Review of Section 230 of the Communications Decency Act of 1996, Dep’t of Just., https://www.justice.gov/ag/department-justice-s-review-section-230-communications-decency-act-1996 (last visited Oct. 23, 2020).

[17] The Times Editorial Board, Opinion: Joe Biden Says Age Is Just a Number, N.Y. Times (Jan. 17, 2020), https://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2020/01/17/opinion/joe-biden-nytimes-interview.html.

[18] Id.

[19] See New IA Survey Reveals Section 230 Enables Best Parts of the Internet, Internet Assoc. (June 26, 2019), https://internetassociation.org/news/new-ia-survey-reveals-section-230-enable-best-parts-of-the-internet/ (putting forth a survey to show that Americans rely on Section 230 protections to a significant degree in their day-to-day use of the internet).

[20] See Derek E. Bambauer, Trump’s Section 230 Reform Is Repudiation in Disguise, Brookings: TechStream (Oct. 8, 2020), https://www.brookings.edu/techstream/trumps-section-230-reform-is-repudiation-in-disguise/.

[21] See Statement on Today’s Executive Order Concerning Social Media and CDA 230, Internet Assoc. (May 28, 2020), https://internetassociation.org/news/statement-on-todays-executive-order-concerning-social-media-and-cda-230/; Statement in Response to FCC Chairman Pai’s Interest in Opening a Section 230 Rulemaking, Internet Assoc. (Oct. 15, 2020), https://internetassociation.org/news/statement-in-response-to-fcc-chairman-pais-interest-in-opening-a-section-230-rulemaking/.

[22] Ajit Pai (@AjitPaiFCC), Twitter (Oct. 15, 2020, 2:30 PM), https://twitter.com/AjitPaiFCC/status/1316808733805236226.

[23] See Ron Wyden (@RonWyden), Twitter (Oct. 15, 2020, 3:40 PM), https://twitter.com/RonWyden/status/1316826228754538496; Pallone & Doyle on FCC Initiating Section 230 Rulemaking, House Comm. on Energy & Com. (Oct. 19, 2020), https://energycommerce.house.gov/newsroom/press-releases/pallone-doyle-on-fcc-initiating-section-230-rulemaking.

[24] 47 U.S.C. § 201(b); Thomas M. Johnson Jr., The FCC’s Authority to Interpret Section 230 of the Communications Decency Act, FCC (Oct. 21, 2020), https://www.fcc.gov/news-events/blog/2020/10/21/fccs-authority-interpret-section-230-communications-act.

[25] Johnson Jr., supra note 24.

[26] 525 U.S. 366 (1999).

[27] 569 U.S. 290 (2013).

[28] Johnson Jr., supra note 24.

[29] See Katie Glueck et al., Allegations on Biden Prompts Pushback From Social Media Companies, N.Y. Times (Oct. 14, 2020), https://www.nytimes.com/2020/10/14/us/politics/hunter-biden-ukraine-facebook-twitter.html.

[30] See id.

[31] See id.

[32] Siobhan Hughes & Sarah E. Needleman, Senate Judiciary Committee Authorizes Subpoenas for Twitter and Facebook CEOs, Wall St. J. (Oct. 22, 2020), https://www.wsj.com/articles/senate-judiciary-committee-authorizes-subpoenas-for-twitter-and-facebook-ceos-11603374015.

[33] See Michelle Gao, Facebook, Google, Twitter CEOs to Tell Senators Changing Liability Law Will Destroy How We Communicate Online, CNBC (Oct. 28, 2020), https://www.cnbc.com/amp/2020/10/27/twitter-google-facebook-ceos-prepared-statements-defend-section-230.html.

[34] Id.

[35] David McCabe & Cecilia Kang, Republicans Blast Social Media CEOs While Democrats Deride Hearing, N.Y. Times (Oct. 28, 2020), https://www.nytimes.com/2020/10/28/technology/senate-tech-hearing-section-230.html (stating that the hearing lasted for four hours and the CEOs were asked over 120 questions).

[36] Malwarebytes, Inc. v. Enigma Software Grp. USA, LLC, 592 U.S. ____ (2020) (Thomas, J., in denial of certiorari), https://www.supremecourt.gov/orders/courtorders/101320zor_8m58.pdf.