By: Ben David*

Introduction

I am a North Carolina prosecutor.[1] I speak for the dead in murder trials and dismiss registration violations in traffic court. I advise police officers in station houses and listen to cooperating criminals in holding cells. When a crime affects us all, I am the conscience for the community, and I give victims a voice at the courthouse. I have been given a vast amount of responsibility, and much is expected of me in return.

I am a graduate of Wake Forest University School of Law. Like most of my classmates, I went to work in private practice and was fortunate to work for a top firm that provided invaluable mentoring.[2] Three years into my legal career, I was able to pay off my student loans while also getting two jury trials under my belt. Like many fellow alumni,[3] I took to heart Wake Forest’s motto of Pro Humanitate[4] meaning “for humanity” and gave up the promise of financial riches in the private sector to become a public servant.

I am an elected official. I am required to simultaneously build alliances with power brokers while making sure that justice applies evenly to everyone without regard to political affiliation. The campaign trail has taken me to every quarter of my community, from million-dollar homes on Wrightsville Beach, to farms deep in rural Pender County, and to community centers in public housing projects.

Additionally, I am the president-elect of the North Carolina Conference of District Attorneys.[5] The Conference holds monthly executive committee meetings where we hear the concerns of the other forty-three elected district attorneys, and we are able to get a view of how justice is served across North Carolina. Like all district attorneys, I am keenly aware that our image has taken a hit over the last five years in both the courthouse and the court of public opinion. Following the Duke lacrosse case, we are in an era where prosecutors have seemingly been put on trial[6] as often as the defendants they are trying, and where criminal defense attorneys have dubbed themselves “advocates for justice.”

I sit on the Chief Justice’s Commission on Professionalism and have been asked to chair the mentoring committee. As many decry the loss of civility and training for new attorneys in our profession, Chief Justice Sarah Parker has realized that, as district attorneys, we often run the largest “law firms” in our communities. Few people have a greater opportunity to mentor law students and new lawyers and to help shape the face of the legal community than district attorneys. Additionally, few areas of the legal profession are in greater need of the best and brightest young lawyers than prosecutors’ offices.

The way forward for our profession, and specifically for prosecutors, is to embrace education and to move toward a model that puts the community at the center of everything that we do. We must remain deeply committed to individuals but must also look at the overall legal system. To be effective, we must be more than great trial lawyers—we have to be problem solvers.

At its core, community-based justice takes an inside-out approach to interacting with the community. As prosecutors, there is a dance we do with the people we represent—we are shaped by the community we live in and are also able to help shape that community by sending messages through policies, verdicts, and outreach efforts. While district attorneys are selected through partisan elections, our policies and actions should not be shaped by political considerations. Rather, we must stay loyal to our oath; our actions should be guided by upholding the law and doing what is right, and not by popular opinion or political pressure.

My district is unique in that there is a large geographic and cultural divide between the two counties I represent. New Hanover County has approximately two hundred thousand people, including many transplants from other places, but the county is the second smallest county in the state.[7] New Hanover County is bounded by beautiful beaches and a historic riverfront district and frequented by tens of thousands of tourists and college students at any given moment. Conversely, Pender County has roughly fifty thousand people, primarily lifelong residents, and is spread out over a large geographic, rural area.[8]

This Essay has two Parts. In Part I, I will explain how I work inside the system by keeping the focus on the community. As the courthouse officials with the greatest amount of discretion,[9] and as some of the only prosecutors in the country with calendaring authority,[10] North Carolina prosecutors have the opportunity to set the tone for their areas. Yet, that power must be shared and used gracefully as we build relationships with others at the courthouse and look holistically at issues to maximize effectiveness.

In Part II, I will focus on going outside the system to work with others in the community on issues that cannot be solved at the courthouse alone. I will highlight a great social issue that has been years in the making and is bigger than any of us: race and justice and disproportionate minority contact with the criminal justice system. It is a problem that can be confronted through a community-based approach that may offer some hope for bringing about long-term solutions. I will also explore how education holds the key to effective community outreach and the role that law schools could play in helping to shape the legal system through an outreach effort to district attorneys’ offices.

I. Inside the System

District attorneys do not represent individuals—we represent whole communities. Under the North Carolina Constitution, district attorneys are responsible for trying each district’s criminal cases as well as advising law enforcement officers.[11] Few people have a better opportunity to set the tone for their area than the district attorney. In my community of just over 250,000 people, there are over nine hundred officers in twenty different police agencies. These officers send five thousand felonies, twenty thousand misdemeanors, and fifty thousand traffic offenses across my desk each year.[12] That translates to thirty percent of the community coming into the courthouse annually. The manner in which these cases are resolved contributes to the public’s perception of justice in our area.

My office’s mission is to protect the public through fair and efficient enforcement of the laws. To achieve this objective, my office prioritizes cases to ensure that violent crimes and career criminals are our primary focus. Broadly speaking, we look for efficiencies within district court (where misdemeanors are handled) and superior court (where felonies are handled) to ensure that justice is swift and, when appropriate, severe. We work closely with law enforcement officers and other courthouse actors with the goal of seeing both defendants and victims walk away from the courthouse feeling that they were treated fairly.

To be effective, I cannot operate in a vacuum but have to reach out to members of the bench and bar. I know that our office belongs not to me, but to everyone who walks into the courthouse. Within a month of taking office, I invited the entire courthouse community—including judges, defense attorneys, bailiffs, and clerks—to the district attorney’s office for an open house around the holidays. To my surprise, this group not only accepted my invitation, but has come back every year since.

I have found that the essence of professionalism is civility. Opposing advocates in the criminal justice system serve different roles and purposes, but can exercise mutual respect in dealings. It is in everyone’s shared interest to leave battles at the courtroom door. The people in my office have attempted to keep an open dialogue, understanding that the vast majority of cases are resolved through plea negotiations where both sides need to be reasonable and have all the facts in order to resolve the cases.

We have also come to see that the problems we encounter cannot be solved alone. There are some issues where defense attorneys, judges, and prosecutors can find common ground—everyone wants justice, fairness, and efficiency. To confront these issues, I meet quarterly in a working group with the Chief District Court Judge, Resident Superior Court Judge, Chief Public Defender, and Elected Clerk of Court in a “Judicial Quarterly Review.”[13] The judges produce courtroom utilization statistics for the prior three months. County commissioners are invited to the meeting to hear from a sheriff’s liaison working in my office how inmates are monitored daily at the jail by a sheriff’s liaison working in my office. Demonstrating this accountability to financial stakeholders and showing our ability to work together to efficiently run the courts have made local funding for our justice system much easier to obtain.

One scholar has referred to community-based prosecution as the process of democratization and decentralization.[14] That is an apt description, as evidenced by the Judicial Quarterly Review. But to me, community-based prosecution refers to more than getting a group together to work on areas of shared concern. It involves being purposeful about how the public is brought into the system as witnesses, victims, and defendants. It also means being intentional about the messages that are sent back to the community through the handling of cases.

Let there be no confusion: district attorneys must remain independent when seeking justice. The notion of the “good old boys” network is an example of how collectively deciding justice at the courthouse can lead to abuse. However, there are instances where the district attorney should work with a larger group of courthouse officials, especially when it involves the efficiency of the system and the creation of specialty courts.

In my district, I have established, either independently or in the courthouse working group, a number of policies to put the public at the center of the process. This community-centered process occurs through the disposition of felonies at the superior court level, the resolution of misdemeanor and traffic offenses at the district court level, applying a mechanism for advising law enforcement, and finally, applying policies within the district attorney’s office to collectively carry out the mission of community-based prosecution.

A. Superior Court

In the purest form, the community is able to speak in the justice system through jury verdicts. Statewide, however, a significant majority of superior court cases are resolved through pleas or dismissals.[15] That means that the few, egregious cases that make it in front of juries must achieve the goal of sending clear messages. Our office is driven by the motto that we try the worst defendants who commit the worst crimes. That translates to trying defendants with serious criminal records and defendants who have committed offenses that have caused the most harm to individuals or society.

North Carolina is one of the thirty-two states where crime victims have a bill of rights imbedded in the constitution.[16] Being responsive to these victims is a high priority for the victim/witness legal assistants (“VWLAs”) and the prosecutors who work in my office. When a violent crime occurs—like rape, armed robbery, or serious assault—my office moves quickly to reach out to victims and give them a voice in the process. This does not, however, mean giving the victims control. We take the responsibility to remain objective and occasionally be the bearers of bad news (such as when a case has to be pled down or dismissed, or alternatively, when we insist on going forward when a victim is reluctant to do so) in order to see that justice is served. This is particularly true in murder cases where the victim is not available to speak for him or herself. Homicide prosecutions are far more likely to go to trial than other types of offenses because the stakes are so high.[17]

It is not only the defendants in homicide cases who receive the highest priorities in my office; the family members of the deceased are also a high priority. To shepherd them through the bizarre and unfamiliar process of a trial, we established the Homicide Family Support Group.[18] The group gathers monthly with the prosecutors who handle the cases in a meeting that is one part informational and nine parts therapy. No one is in a better position to counsel a grieving family who recently experienced the loss of a loved one through a brutal murder or vehicular tragedy than a family who had a similar loss and went through the court process. Prosecutors and VWLAs are there to answer general questions about the road ahead without discussing the confidential, specific facts of each case until individual meetings. When the cases go to trial, it is not uncommon for the whole group to attend in support of the family. Immense healing takes place and trust is built during these meetings. This program is now being replicated throughout the country.

Murder cases are often high-profile cases that receive public scrutiny. Nevertheless, for victims whose cases do not receive media attention, our duty to seek justice is just as important. Just as no one is above the law, no one is beneath its protection. While it has frequently been said that “bad things happen to good people,” we far more frequently encounter victims who were engaged in criminal conduct at the time of their victimization. When a prostitute gets raped or a drug dealer gets killed, it is our responsibility to reach out to these victims and their families just as we would any other victim of crime. As will be discussed in greater detail, victims and witnesses are far more likely to come forward if they know that they can get justice at the courthouse regardless of their status. Simultaneously, we hope that the community, through its verdicts, comes to uphold the principle of equal protection under the law.

We also identify drug traffickers and dealers for vigorous prosecution. While the consensual sale of illegal substances may seem, on the surface, to be a victimless crime, the reality is far different. Apart from the fact that many users ultimately destroy or end their lives through drug use, the community immediately surrounding the drug trade often suffers collateral damage. This is especially true in economically depressed areas and public housing projects.[19] My office views these neighborhoods not as “high crime areas” but as “high victim areas.” Drugs are the fuel for the engine of violent crime and often lead to turf wars, armed home invasions, and the formation of street gangs. These secondary consequences of the drug trade can destroy whole neighborhoods.

My office not only seeks maximum justice in state court for these cases but, where appropriate, takes these cases into the federal system. Five years ago I formed a partnership with the United States Attorney for the Eastern District of North Carolina, George Holding,[20] to apply for grant funding to allow my office to hire a senior prosecutor to be cross sworn to handle drug cases in the federal system. The success of this partnership has been dramatic from the standpoint of prison years for serious offenders and the amount of weapons and drugs removed from the street. Not only has the grant been renewed each year but the program is now being replicated by other district attorneys throughout the three federal districts of North Carolina.

B. “H and I” Court

There are a great number of felony cases involving defendants who are not bad people, but rather, people who have made bad choices or have substance abuse problems. For these nonviolent cases, usually involving property offenses and drug possession, the best disposition may not be found in superior court. North Carolina established a law to resolve these low-level felonies in a special district court, without the need for indictment.[21] Not all districts employ this court, sometimes named the “H and I court” after the classes of eligible offenses, but our district would scarcely be able to operate without it.

When one of the over five thousand felony cases comes to district court for a first appearance, every file is looked at by one of two career prosecutors who have a combined experience of over fifty-five years in our district.[22] If the case clearly calls for grand jury indictment, the case is diverted to the rest of the team in the superior court division. The remaining cases, typically over two thousand each year, are resolved in felony district court.[23]

There are two large benefits from the H and I court. First, efficiency is greatly increased as minor cases bypass the grand jury, and superior court prosecutors are able to focus their time and resources on the violent and career criminals. Second, many of the defendants whose cases are resolved through H and I court are given a chance to have either a misdemeanor or deferred prosecution that might not impair their ability to be productive members of society.[24]

C. District Court

District court is frequently referred to as the “People’s Court,” and for good reason. Every year thousands of cases come through the door, including minor traffic offenses, property offenses, underage drinking, and assaults. Nearly all of these cases are initiated by police agencies, though North Carolina law allows for private citizens to charge each other.[25] Assistant district attorneys encounter hundreds of cases each day and have to make quick decisions about how the community gets justice. Setting priorities and managing time become central to effective prosecution in district court.

There are two classes of misdemeanor cases that kill people: impaired driving and domestic violence. In the Fifth District we average over three thousand driving-while-impaired (“DWI”) cases annually and over one thousand cases of domestic violence, in addition to over seventy-five thousand other cases.[26] Because these cases go to trial before a district court judge far more often than other types of cases, ensuring court time for these cases is challenging.

To help alleviate the problem of overcrowded dockets we filter out all of the minor traffic offenses. In 1999, when I started as an assistant district attorney in New Hanover County, we implemented an “Administrative Traffic Court”[27] to handle compliance-based offenses (such as registration or inspection violations), moving violations (such as speeding or running a stop sign), and traffic accidents. The court meets every Friday morning and handles anywhere from eight hundred to twelve hundred cases. No judge sits on the bench and no officers are subpoenaed to court; instead, several prosecutors and VWLAs join with deputy clerks to encounter the masses. In keeping with the priority of convicting the worst defendants, officers are advised not to set cases in traffic court that involve defendants with bad criminal histories or involve serious moving violations (such as DWI, driving during revocation, or reckless driving).

In traffic court, defendants are told that if they would like to contest their cases, or if they would like an attorney, the state will continue their matters to the officer’s court date. Otherwise, they will be treated no differently than if they had a lawyer. Depending on the violation, compliance-based offenses are typically dismissed upon proof of the driver having his car registered or inspected. Those accused of moving violations are either sent to driving school, with a special emphasis on educating young drivers,[28] or dealt with through a disposition that allows defendants to pay fines and court costs. Depending on their records, defendants charged with traffic accidents will either have their cases dismissed or be sent to driving school if they provide proof of insurance. The vast majority of the community leaves court having had their cases disposed of within mere minutes (as opposed to hours if they were in district court), without the need for an attorney, and with the view that they were treated fairly. The court has proven so successful that it became the law in October 2011.[29]

Because there is now more court time available to hear impaired driving cases, our district has set up a DWI court. DWI cases either go to trial or plea because of our “no drop policy.” As an additional issue, many defendants charged with these offenses have substance abuse issues. We understand the reality of alcohol and drug abuse and the need to treat abusers rather than just incarcerate them, and have therefore sought to set aside time to bring in habitually impaired drivers and their family members to resolve their cases in a way that focuses on long-term probationary sentences. This approach should not be viewed as going easy on crime—defendants who are convicted of impaired driving offenses will only serve about thirty days of a two-year sentence under current Department of Corrections policy.[30] Rather, this approach protects the community through a focus on long-term treatment that may actually end the cycle of abuse.

Treatment courts understand that defendants with underlying substance abuse issues will continue to go through the revolving door of the criminal justice system if their dependency issues are not addressed. Every two weeks, defendants stand before the same district court judge and, together with their probation officers, give an update on the defendant’s work history, treatment sessions, and drug test results. The court often shows great latitude, but to get the defendant’s attention, the court may give defendants short jail sentences without revoking their probationary sentences. After one year of living drug or alcohol free and complying with all of the standard terms of probation, defendants “graduate” from the program in an elaborate ceremony celebrated by all participants. Judges and prosecutors have become so convinced of the value of this program that when state funding for the program was cut for the 2011-2012 fiscal year, county funding was obtained to continue the drug court’s operation.[31]

Domestic violence cases are among the most difficult in the court system. Interfamily violence often remains hidden and is frequently only discovered after a major crime of violence occurs. In 2004,[32] I created a family violence unit in our office that consists of two full-time prosecutors and a VWLA working with three detectives who are housed within the same office. Victims are told about our unit when they go to the courthouse to obtain a civil domestic violence protective order. Victims are counseled about the availability of a twenty-four-hour domestic violence shelter, and detectives investigate whether criminal violations have occurred. The unit is on hand to follow up with photographs of injuries and collect physical evidence to preserve for future use at trial. Following up and following through on these cases—especially with reluctant victims—has greatly increased law enforcement’s ability to hold offenders accountable and to prevent future, possibly more serious interfamily violence.

District court is also the venue for resolving juvenile offenses. The severity of some of these crimes, including rape and murder, requires prosecutors to bind juveniles over to superior court to be tried as adults. North Carolina is one of only two states where sixteen is the age of juvenile jurisdiction, so binding a young person over is rare, even with the most serious offenses.[33] Far more common are cases, even involving young adults attending area high schools and colleges, which scream to be resolved through teachable moments that should not lead to a criminal record.[34] For first-time offenders of nonviolent misdemeanors, we created Teen Court in 2000. Cases are diverted from the juvenile justice system and put in Teen Court where every participant, including the prosecutor, defense attorney, and members of the jury, is also a teenager. The only adult in the process is an attorney serving as the judge. To qualify for Teen Court, the defendant must admit liability so that the “trial” is really a protracted sentencing proceeding where the jury is given a range of options for a community-based punishment. The numbers show that Teen Court has reduced recidivism and allowed many young people to learn about the justice system through a positive experience.[35]

While we work hard not to sacrifice effectiveness in the name of efficiency, we have put systems in place in the Fifth District to move the community through the courthouse so that minor cases may be resolved without tying up the time of judges, officers, and juries. Court time in the district and superior court divisions is reserved for cases where justice cries out for a full airing of the facts in an open courtroom. We temper justice with mercy and, where appropriate, place people on probation or defer prosecutions to keep their records clean. In both treatment courts and administrative traffic court, our goal is to resolve underlying problems rather than brand a citizen a criminal. For the defendants and offenses where that is not possible, we use our time and energy to impose the full measure of the law.

D. Law Enforcement

As the “top cop” in the district, the district attorney has a great opportunity to shape the policies and procedures of the police agencies through the constitutional mandate to advise local law enforcement.[36] In the Fifth District, there are over nine hundred sworn law enforcement officers in twenty different police agencies. While many of these agencies have embraced the emerging national best practice of community-based policing,[37] I will briefly focus on the relationship that I try to maintain with members of law enforcement as we jointly uphold our respective oaths of serving and protecting the public and defending the North Carolina Constitution.

First and foremost, constant communication is vital in order to have our priorities on the street translate to priorities in the courtroom and vice versa. To that end, I personally hold monthly lunches with the heads of all police agencies to give them legal updates, hear their concerns, and keep the lines of communication open between all the agencies. Second, we employ technology to get daily updates about arrests from the night before through “Watch Commander’s Reports.” Prosecutors use this information at the first-appearance stage to assist in setting bonds and calling for follow-up discovery. Finally, law enforcement liaisons within my office call officers in emergency situations, or have them on standby, in the event they are needed for trial so that they can remain on the street until they are needed.

We employ a police-and-prosecutor team approach to fighting crime. All officers have the contact information of my senior assistant district attorneys. They can call at any time to get legal advice on substantive charges and procedural issues that arise in the course of their investigations and arrests. I have a district attorney investigator who is sworn to assist the police agencies with follow-up investigation and to bridge the gap between the probable cause for arrest and the proof beyond a reasonable doubt necessary for a conviction. Additionally, prosecutors and investigators in my office visit crime scenes and go on ride-alongs to see firsthand the conditions on the street.

Training is also an essential component, and we attend lineups and conduct mock trials for basic law enforcement training. A push is currently in place to have elected district attorneys and senior assistant district attorneys become certified as law enforcement instructors.[38] Teaching officers good habits at the beginning of their career engrains in them the culture of doing justice and not simply convicting at all costs. It is unquestionably better for the system if defendants’ rights are upheld at the time of search and arrest rather than if evidence is suppressed—and the community’s confidence compromised—because of an unconstitutional application of the law.

Despite the close working relationship between my office and law enforcement, we must always assure the community that we are independent agencies with separate functions. When an officer has “tarnished the badge” by committing a crime, he is prosecuted by my office in the same manner as any other defendant. Off-duty criminal conduct by officers is not tolerated by either my office or the larger law enforcement community, and those defendants receive no preferential treatment.

When an officer commits a crime or becomes the victim of a crime in the performance of his or her duties, public scrutiny becomes especially intense. In these types of cases, which typically involve use of force or high-speed pursuit, a certain Bermuda Triangle is formed between the district attorney, the officer and his colleagues, and the community, as perceptions form over whether justice can truly be done. Different factions may scream for leniency or maximum punishment, reactions based more on agendas and relationships than the facts of the case. In these situations, the key for building and keeping trust among all parties is to remain independent and transparent while maintaining a commitment to doing the right thing.

Protocol never changes for cases that involve the law enforcement family. When an officer is the victim or defendant in a serious felony, I call for an outside investigation by the State Bureau of Investigation (“SBI”). If felony charges are to be lodged against an officer, they come not from prosecutors but from the grand jury.[39] The same is true when a defendant is charged in the death of an officer.[40] While these cases divide the community, it is the community who ultimately speaks through its verdicts. Finally, when there are no charges and no grand jury is impaneled, I release a detailed synopsis of the investigation to the press and invite a member of the deceased’s family and his or her attorney to review the complete file and interview the lead SBI agent.[41] While it would be easy to duck from the responsibility of handling these controversial cases, I personally involve myself in their prosecution and only refer the case to an outside prosecutorial authority in extraordinary circumstances.[42]

Ultimately, cases are only as strong as the investigations brought to the courthouse. Therefore, it is vitally important for prosecutors to be engaged in the training of police and to maintain an open line of communication with them. This close working relationship cannot, however, degrade the independence that each agency must have in the performance of its respective duties. When officers enter the criminal justice system as victims or defendants, the community must be put in the middle of that relationship in order for public trust to be maintained. Finally, the community is made a partner in finding solutions to the problems that police and prosecutors encounter in their jobs

E. Inside the District Attorney’s Office

The district attorney’s office in the Fifth District is actually the largest “law firm” in our area. In fact, you would have to travel two hours up the road to New Bern or to Raleigh to find a larger collection of lawyers in one office. With just over forty people, evenly divided between attorneys and staff, our policies and practices help set the tone for the larger legal community—a group of over seven hundred attorneys in Wilmington alone.

Getting everyone in my office on the same page of community-based prosecution is a purposeful effort that takes many forms. First, we employ a philosophy that respects everyone’s views in the office, regardless of status or level of experience. We run on the principle that “nothing is above you and nothing is beneath you.” That means that both the most senior assistant district attorney and the newest VWLA are expected to be responsive to the public by returning calls the same business day, fielding citizen concerns and complaints as they arise, and engaging with all aspects of our community. It also means that there is no hierarchy in taking on a terrifying amount of responsibility in big cases.

To give everyone a shared sense of the mission of the office, everyone reads and signs an eight-page employee manual that lays out our expectations. Employees are reminded that they represent the office at all times—at work during the business day, at home, and out in the community when the work day is over. We enforce five core values: respect, honesty, responsibility, transparency, and trust. Everyone rereads and signs this manual annually just before he or she receives a yearly employee performance appraisal.

On Monday mornings I hold a weekly meeting with the entire office to give individuals the opportunity to share information with the larger team. The meeting begins with the assistant district attorneys and VWLAs giving a summary of the cases they resolved, through trial or plea, from the week before. I have found that this gives the whole office ownership of these cases and gives accountability to the individuals who handled each case. Praise is given in public, and any problems that surface during this process, such as courts breaking down early or unacceptable handling of cases, are addressed in private. We also look at the week ahead and discuss the cases and events in the community that everyone should anticipate. People step up to cover different courts or community events so that everyone in the office stays connected to the idea that he or she individually has a stake in the whole.

I also hold a Thursday morning meeting with the attorneys to prevent silos from developing and discuss issues with calendaring and court coverage. There are six work groups by case type: violent crimes, drug offenses, property and financial crimes, motor vehicle offenses, sex crimes, and domestic violence. The attorneys also jointly analyze the legal complexities that arise in some of their cases and seek each other’s advice. Cases are sometimes reassigned at these meetings, or someone may volunteer to be a second chair to assist with trial preparation. Attorneys take ownership by understanding that all the cases belong to the office and at any time they may be called on to handle, or assist in handling, a matter even if it falls outside their assigned areas.

Managing attorneys is a notoriously difficult task. While some have referred to it as “herding cats,” I believe it is, as former President Bill Clinton said of being president, more like “running a cemetery; you’ve got a lot of people under you and nobody’s listening.”[43] I respect the views of coequal professionals and do not bog them down with numerous written policies or micromanagement by senior staff. Instead, everyone is vested with a large amount of discretion, and he is told that he should not act unless he would feel comfortable explaining his actions (such as plea offers he has made or advice to law enforcement he has given) to the community we all represent.

The lifeblood of my office is the people who work in it. To recruit the best and brightest attorneys and staff, my office is very intentional about the intern program we have established. Years ago I partnered with the local university, University of North Carolina Wilmington, to allow third- and fourth-year students to obtain course credit if they extern for 150 hours a semester in our office. Each fall and spring semester, college interns are paired with individual VWLA mentors to carry out support staff tasks. Many alumni of this program have gone on to law school or have been hired by our office as full-time employees upon graduation.

For law school students, we have set up a summer internship program that brings a mix of rising second- and third-year students. Second-year law students are partnered with assistant district attorneys at the superior court level and assist with case preparation and legal research and writing. Third-year law students get certified for the third-year practice and are partnered with assistant district attorneys at the district court level to assist in running the court. Third years are also able to try some misdemeanor cases. Because of the great demand for our intern program, and so that students’ experiences are not diluted—we have divided the summer into two sessions and have no more than ten law students working in the office at any given time. Most of my assistant district attorneys have come through this program, and at least ten former interns have found placement in other districts.

We try to connect the undergraduate and law student interns to the larger courthouse working group and community we serve. At the beginning of the summer, for example, I host a welcome reception in my backyard where students are able to mingle with judges, clerks, law enforcement officers, and defense attorneys before they begin their work. Throughout the internship experience, we also send students on field trips to see the larger community. These experiences include going to the jail, traveling to the SBI crime laboratory in Raleigh, touring a local drug treatment center, meeting with court advocates at the domestic violence center, and going to a shooting range with sheriff’s deputies.

Just as it is vitally important for prosecutors to stay connected to others inside the system, it is at least as important for prosecutors within an office to stay connected to each other. Being intentional about recruiting, retaining, and training has made it easier to promote the community-based prosecution model that I employ in the office. Focusing on education allows my prosecutors to stay connected to the officers we advise through cross training and legal updates. It also allows my prosecutors within the office to focus on the fundamentals of our profession and stay abreast.

Education is also the cornerstone of the work we do outside of the criminal justice system. Ultimately, the biggest issues that confront prosecutors in the community are often solved or prevented in an educational setting. It is to those efforts that I now turn.

II. Outside the System

As a district attorney, part of my job is crime prevention. To achieve this end, I try to meet at-risk youth where they live and have a conversation about choices and consequences before they get in trouble. For victims, I encourage them to report their victimization to help break cycles of violence.

Community outreach is not a task that I do alone. Every one of my employees is allowed to take every other Friday afternoon off if he or she volunteers two hours each week to work with individuals who are, or might be, potential victims or defendants. On nights and weekends, members of my office serve in roles as diverse as being basketball coaches, being reading tutors, or answering calls at the twenty-four-hour rape crisis hotline.

We also target certain areas of our community for increased enforcement. Take, for example, the downtown tourist area on the River Walk of the Cape Fear River. With eighty bars, shops, and restaurants packed into a central business district that spans only a few blocks, it is easy to predict that there will be crime. Preventing an impaired driver from causing fatalities through checkpoints pays immediate dividends.[44] Bars that become crime magnets for repeated violations, such as underage drinking and bar fights, receive a letter from me that they are being monitored.[45] If the lawlessness continues, I file a suit in civil court to close them down.[46] This active participation in enforcement efforts has led to a large decrease in crime in our central business district.[47]

For the cases involving societal ills like domestic violence, sexual assaults, and child molestation, underreporting is a problem. Breaking the well-documented cycle of abuse is at the core of my prevention strategy. Left unchecked, the abuse continues and ultimately gets perpetuated onto the next generation. Local efforts to break this cycle and establish a support network to bring these cases out of the shadows and into the sunlight receive my full attention.

Community outreach should be distinguished from attending political functions or becoming active only at the height of a political season. On the contrary, winning public confidence is not an event; it is a process. This is a new day in North Carolina where many of the elected DAs are constructing their offices from the ground up.[48] The modern trend is for us to be less political, not more.[49] Party labels should matter no more for the DAs[50] than the political parties of the victims and defendants who come through the system. The fact that I have been unopposed in the last two elections is the ultimate vote of confidence and confirms that my office’s outreach efforts transcend the political arena.

Outreach at local schools is also important. Since being elected district attorney, I have made yearly visits to every public middle school and high school in my district to talk to the students about being responsible and doing the right thing. Eighth graders hear about bullying, dangers on the Internet, and saying no to drugs. Twelfth graders also hear about some of these subjects, especially drug laws, while also receiving a good dose of real-world perspective regarding the laws surrounding driving and relationship violence. I also devote several nights each year to meet every incoming freshman at both the University of North Carolina Wilmington and Cape Fear Community College to welcome them to a new community and introduce them to the expectations we have for them as adults. While the content may vary based on the age of the crowd, my theme of being a leader is unwavering, and I try to give concrete examples that my audience is likely to encounter and encourage students to report crimes. If students are being bullied at school or being touched inappropriately at home, they must report it. If they have stumbled across an online predator, they should not try to ignore it; they must tell a parent.[51] Many have responded by reporting their victimization or that of others following our talks.

Through this outreach effort, I have attempted to encourage young people to take ownership in their community and to be involved in their own safety. I have been amazed by their leadership and willingness to reach out for help, instead of suffering in silence, when they have been victims and witnesses. But sadly, I have seen that with these young people, and their parents and grandparents too, there remains a broad category of unreported crimes that never reach the criminal justice system.

Street-level crime—from drug dealing in open-air transactions, to violent crime and gang activity—still goes largely unreported. In the “stop snitching culture” that pervades our inner city, today’s victim (for example, a victim who is shot in the leg for dealing on the wrong corner or wearing the wrong colors) becomes tomorrow’s defendant as he seeks vigilante justice in retribution for his earlier victimization, perpetuating a seemingly never-ending cycle of violence. The victim’s silence at the hospital speaks loudly about the mistrust he has in the justice system—a system with which he has likely had personal experience and a system that has likely incarcerated members of his family. For this victim-turned-bounty hunter, his view is simple: if he cannot find justice at the courthouse, he will look for it in the street.

A. Race and Justice: Confronting the Sleeping Giant

The D.A. is inevitably in daily collision with life at its most elemental level. His job is somewhat akin to that of a young intern on a Saturday night ambulance call: he is constantly witnessing the naked emotions of his people—raw, unbuttoned, and bleeding . . . . By virtue of his job the D.A. is the keeper of the public conscience . . . .[52]

Some years ago, after a racially charged killing occurred in my community, I asked my sheriff to look at the people who were incarcerated at the New Hanover County Jail. We found that of the 520 inmates, 54% were African American.[53] That was three times what would be expected if the county-wide demographic of 18% African American held up on a one-to-one correlation. A look at serious crimes of violence made me only more disheartened. Of the pending 34 murder cases, 30 involved African American defendants. The numbers were equally staggering for assaults with a deadly weapon (25 total, 16 African American); sex crimes (29 total, 13 African American); armed robbery (40 total, 28 African American); and drug trafficking offenses (37 total, 22 African American).

These numbers are alarming for many reasons. First, there is a theory that defendants tend to pick victims that look like them,[54] and this theory would suggest that if most of the defendants in the system were from a particular minority group, so too would be the victims of their crimes. This dread was confirmed: of the 30 aforementioned African American murder defendants, 29 of their victims were African American as well.

Another reason for concern is that African Americans are underrepresented in the criminal justice system. The majority of attorneys, judges, and law enforcement officers are white. Any trust issues that underscore this divide could result in underreporting of crimes if African American victims do not feel that the justice system is at work for them.

What do we do when the population most affected by crime does not want to participate in the criminal justice process? As Attorney General Eric Holder recently suggested, maybe we are not taking any risks at all.[55] But if those of us in the system believe, as I do, that we have a duty to speak the truth to our community in the same way we speak the truth in court, then something must be done. I will now discuss the two ways a district attorney can reach out to the community to confront this issue: first, an approach that does not work, and then an approach that does.

B. Agenda Driven Outreach: Playing Politics with Cases

On a beautiful spring day in April of 2007, the relative calm of Easter weekend was thrown into turmoil with the loud popping of gunshots on the north side of Wilmington.[56] For the crowd that gathered outside the Creekwood Housing Community, a public housing complex where crime has run rampant for years, the early stages of a cover up appeared to be in the works. On the ground was the naked and lifeless body of Phillipe McIver, a young African American man with an extensive criminal record. Two armed, white Wilmington Police Department officers stood over him. As officers patiently waited for SBI agents from outside the city to arrive to handle the investigation, some members of the crowd began firing shots into the air. A police tactical team had to come in and disperse the crowd.

Fear hung in the air in the days that followed. Rumors swirled that there might be city-wide riots. Marches took place. Some walked with signs that read “Just Us” to refer to the prospect of getting “justice” against cops. And at the height of it all, a group of concerned citizens came to me with a plea to pursue the officers to the fullest extent of the law. These leaders were men and women whom I had admired: heads of the NAACP, of which I am a member; pastors and bishops who preside over huge congregations of law-abiding citizens; and political allies who helped me get elected. In the middle of the group was a woman who had just lost a son, Ms. McIver. I spoke with Ms. McIver and asked her to join me in calling for calm. Together, we held a press conference to call for calm. And for the moment, everyone listened.

If there was ever a time for using a case as an opportunity to build trust with a disenfranchised segment of the community, this was it. Here was an opportunity not only to get justice for Mr. McIver but for all other similarly situated victims who did not have a celebrated case attached to their names. The community was, and would be, watching. The group of leaders who had come to my office wanted me to send a message they had heard me say many times before: no one is above the law, and no one is beneath its protection.

There was only one problem with prosecuting the officers who fired the lethal shots—they were innocent of any crime. The shooting, as our investigation showed, was justified. In-car cameras captured the events, and toxicology tests later confirmed that McIver was high on “love boat,” a combination of marijuana and formaldehyde, and sitting naked in the street, blocking traffic at the time officers approached him.[57] As they attempted to remove him from the road, McIver wrestled one of the officers to the ground, removed the officer’s service revolver, and began shooting at him at point-blank range. The other officer then shot and mortally wounded McIver in defense of his partner. Both officers then secured the scene, including removing the weapon from McIver’s hands, before the crowd came.[58]

Prosecutors must start with the facts and not theories. When they start with agendas and theories and then bend the facts to suit those theories, the results are disastrous. At the very moment that I was handling the McIver case, another district attorney was having a similar discussion with his community about race and justice just up the road in Durham, North Carolina.

Durham’s district attorney, Mike Nifong, was embroiled in a political race, and many have speculated that his rush to judgment in seeking an indictment against four white Duke University lacrosse players accused of raping an African American entertainer had more to do with pandering to his base than getting justice.[59] What would become clear over time is that Nifong had not properly vetted the case nor had he done the necessary background investigation prior to publically staking himself to a position. Instead, he began a community quest to slay the larger giant using the well-established teaching tool of the case method.

North Carolina prosecutors, especially other elected district attorneys, watched the train wreck in horror. Some of the more senior elected district attorneys offered to take over once it was apparent that Nifong could no longer remain objective.[60] When Nifong did not accept this advice, the Executive Committee of the North Carolina Conference of District Attorneys, of which I am a member, took the extraordinary step of writing an open letter to Nifong calling for him to step aside in the interest of justice.[61] Nifong’s subsequent disbarment made international news.[62] The damage, in our view, was detrimental not just to Nifong but also to everyone in the criminal justice system, especially prosecutors. Ultimately, the case has become synonymous with district attorneys playing politics and trying cases in the media instead of at the courthouse. As I noted earlier, ethics violations filed against prosecutors have increased ten-fold since this case.[63]

Prosecutors are not the only ones who play politics with cases, however. One need not leave the campus that gave rise to the Duke lacrosse scandal to see another example of how some exploit race to manipulate an outcome in a criminal case. In September of 2004, the Center for Death Penalty Litigation, led by an adjunct faculty member at Duke, sought to have a recent death penalty conviction I had obtained a week earlier overturned on the grounds that I tried the case for political motives.[64]

At the time the motion was filed, I was running against three defense attorneys in a special election to replace the retiring district attorney. The election was to take place two days after the motion was filed. The motion, which was sent to the press and passed around the African American community, accused me of being racist and compared me to a former district attorney from the same district who had lost his job after uttering a racial slur.[65] The motion was heard three months after the election by the same superior court judge who presided over the trial. In a scathing eight-page order, following a four-day hearing, Judge Jerry Cash Martin found that the motion was “blatant political sabotage.”[66] The professor who lodged the allegation was fired, and Duke has since severed connections with the Center for Death Penalty Litigation.[67]

It would be nice if the recent painful history of mixing race, politics, and the death penalty was in the past, but that is not the reality. Recently, a new debate has been waged over the Racial Justice Act.[68] While the Act has a laudable title, the application has been disastrous. District attorneys have united against it, risking condemnation and being labeled as racists by advocates more interested in abolishing the death penalty than ensuring justice in individual cases.[69] Sadly, the chasm that has been created between district attorneys and the communities we represent, especially the African American communities, has grown as this emotional issue has been exploited for political purposes.

C. Elevating the Conversation: The Professor and the Gospel Singer

As I was deciding how best to address the larger community discussion that was taking place in Wilmington over the McIver shooting, I traveled to Durham to see my mother. She lived five houses from the Duke lacrosse house and was closely following the case. When the opportunity came to attend a public forum hosted by her alma mater, Duke University, she quickly registered and invited me to attend with her.

While Nifong had launched his own effort to “heal Durham,” Duke embarked on a similar quest using a much different approach. In an effort to create a community-based discussion around the thorny issue of race and justice, Duke enlisted the assistance of Professor Tim Tyson. Dr. Tyson, who is white, majored in African American studies and has gained a national reputation for writing about the civil rights struggle both in learned treatises and in novel form.[70] The son of a preacher,[71] Dr. Tyson approached the issue of race relations with a fervor that bordered on religious zealotry and considered equality for all people to be a moral imperative.

Dr. Tyson’s approach was cutting edge and bold in its execution. Instead of having an academic lecture on Duke’s campus (that few would likely attend), he opted instead to teach a “class” of three hundred students,[72] diverse in every respect, at the Hayti Heritage Center, a historic African American church. One hundred community leaders, including my mother, were also invited to audit the eight-week offering that would explore the history of race and justice in Durham in three-hour sessions. One night might have been devoted to the Greensboro sit-ins while another night might have involved relations in Durham during the World War II era. At the end of Dr. Tyson’s talk, which usually lasted about an hour, he would moderate a panel of local leaders who would provide their own first-hand accounts. A third hour was devoted to either an open microphone discussion with the whole class or breakout sessions in small work groups for community-based action on current issues.

To underscore the point that the purpose of the gathering was not merely an academic exercise, Dr. Tyson elevated the conversation by inviting a gospel singer to teach the class with him. Mary Williams, with a powerful singing voice reminiscent of Aretha Franklin, could take over the room from the moment the class began. With a force that has to be experienced to fully appreciate, Ms. Williams drew everyone into singing well-known songs from the civil rights struggle and hymns from the slave era. When the songs were finished, Williams began a lecture about the oral history that was transmitted through the music. In doing so, she peeled back the secret codes and buried lessons in a different way of learning that inspired the crowd in a way that Dr. Tyson could not do alone.

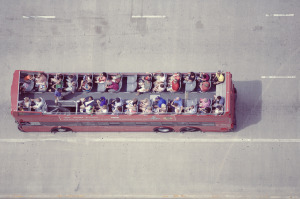

Within minutes of watching the class, I knew that I had found a much better vehicle to engage in community outreach in Wilmington. Over the next several days, I met with the same leaders who had come to my office after the McIver shooting. I encouraged them to come with me to Durham to see firsthand what I had witnessed and rented vans to bring sixteen of them to the next class. All were similarly impressed and agreed to approach Dr. Tyson and Williams about replicating the class in our community. Both were excited by the opportunity and intrigued by the idea of working with a district attorney on the issue, rather than working to undo the damage a district attorney was causing. Both said yes.

Dr. Tyson grew up in Wilmington, witnessed its racial history firsthand, and became a celebrated author in chronicling it.[73] Going back over one hundred years, a great divide had been created in our community along racial fault lines. While once a shining example of racial equality in the Jim Crow South, the city’s black middle class was run out of town in 1898, and black elected leaders were forced to resign at gunpoint in the only coup d’état in American history.[74]

Seventy years later, tension again boiled over when African American students were relegated to second-class citizenship when their school, Williston High School,[75] was closed to comply with desegregation laws brought about by Brown v. Board of Education.[76] The race riots that followed that painful chapter of Wilmington’s history spawned the celebrated case of the Wilmington Ten, in which African American defendants were initially convicted of firebombing a white-owned grocery store and then were later pardoned by the governor.[77] While much of this history was never documented in school textbooks, it was handed down in an oral tradition, especially in the African American community in Wilmington, which left a lingering mistrust of established power a century later.

The group that went with me to Durham was called the “Big Picture Talkers.”[78] Our goal was to bring together the unofficial leaders of the community—public educators, pastors, and heads of nonprofit agencies. We were not looking for an event but for the beginning of a process, one that would reflect the words of the mission statement: we are committed to bringing together a new multicultural community in order to create a space and the time to dissect, discuss, and confront Wilmington’s racial history. Furthermore, we wanted to attempt to understand history’s persistence in the present and its possible effects in the face of the future. Our purpose was not only to wallow in our city’s painful history but also to celebrate its many triumphs and highlight the incredible achievements of our residents.[79]

The class we created, “The History of Wilmington in Black and White,” was held in the old Williston High School building to underscore its historical significance. First-year attendance numbered over three hundred, all from the community—as opposed to just from the local colleges. Now going into its fifth year, our goal is to have one thousand graduates. The class is funded through grants from the Z. Smith Reynolds Foundation and is run through the YWCA.[80] The friendships that have formed out of this shared experience survive the end of a semester, and the relationships formed have turned into community action. As a result, people inside and outside the criminal justice system affect change in our community.

The Big Picture Talkers, like Dr. Tyson and Williams, recognized the incredible organizational power of the church, especially in the African American community, as a way of spreading the message of reconciliation and elevating the debate beyond the political realm. The pastors who I had befriended and who helped keep the community calm following the McIver shooting knew the power of the truth: murder is the leading cause of death in North Carolina for African American males under the age of twenty-four, and they are 4.5 times more likely to die of a homicide than their white counterparts.[81] The pastors looked at crime prevention as a moral issue. As Pastor Rob Campbell of New Beginnings Church in Wilmington has said to me, these are not black children or white children dying in the streets of Wilmington but “God’s children.”

The clergy also knew that their congregations were the most segregated part of our community.[82] They committed to leading by example to help end the divide by hosting each other’s congregations in their respective churches. Results were celebrated. Eight pastors from some of the most established churches, four white and four African American, formed a joint bible study to give “The History of Wilmington in Black and White” students yet another way to learn from each other and form a bond.

In time, the various congregations adopted a home through Habitat for Humanity to construct together. Additionally, one of the established congregations donated the resources of its church. The congregation had recently purchased the building that formerly housed the county jail and turned it into an outreach center for gang prevention and work placement for the homeless.[83] In short, these pastors put their faith into action and became great allies for the community—an outcome that no verdict alone could deliver.

D. Bringing Leaders Together: Ideas Into Action

The judges, defense attorneys, deputies, and elected leaders whom I worked with to improve courthouse and jail efficiency wanted to break the cycle of violence where street-level crimes were going unreported. They had observed the success of the Big Picture Talkers and were eager to build on that momentum. Part of the solution involved making it easier to report crime and to protect informants once information was given.[84] But for reporting to really take place, victims and witnesses had to believe in the justice system and trust in its ability to protect them.

These public officials knew that, while we had the responsibility to lead, we had to go beyond the courthouse or the political realm. We also knew that there would be no quick-fix solution but instead there would be years of work—years that would outlive election cycles or grant funding. To these ends, we invited into our group four distinct parts of the community, who also had a stake in helping us confront this issue: business leaders, religious leaders, school officials, and nonprofit organizations. The result was the Blue Ribbon Commission on the Prevention of Youth Violence (“BRC”).[85]

The business leaders understood that crime greatly influenced the quality of life and that the reality or perception of crime in the downtown business district greatly impacted our ability to attract investment. They also knew that displacing crime to another area of the community would not solve this issue for the entire area.[86] The head of the Greater Willington Chamber of Commerce was made a part of the BRC and has worked to engage this vital part of the team by hosting power breakfasts, applying for grants, and encouraging corporate investment in our prevention efforts.

The religious leaders, who came together around the movement of the Big Picture Talkers to start a unity and reconciliation effort, were also made part of the endeavor. Two pastors, one from an established African American church and the other from one of the oldest and largest white congregations downtown, were each given a place on the commission.

The school superintendent was also invited to join the team. He was facing the same racial divide with greater suspensions and dropouts, and a “minority achievement gap.” If there was a part of our community where fence mending was needed to confront our present by looking at our history, school officials knew they had a role to play.

There were over forty nonprofit groups working directly with the at-risk youth we were seeing at the courthouse. Many of them had been doing incredible work in diverse areas such as Boys and Girls Clubs, after-school arts programs, and gang intervention programs. While they all had the same desire to help, many of the groups were in direct competition for scarce grant dollars. In an attempt to bring the groups together behind a common cause, we gave them a seat at the table by forming a distinct arm of the BRC, known as the Tactical Advisory Committee, and invited the local director of the United Way to join the board.

With the BRC now established, we hired a strategic director from the community to work full time on the effort. We created three subteams to focus on specific areas. The Youth Violence Action Team was tasked with reducing crime by twenty-five percent over the next three years. The Education Action Team was tasked with reducing out-of-school suspensions and the dropout rate by twenty-five percent over the same time period. The Community Engagement team was charged with enlisting a volunteer army of four thousand and promoting our efforts to the larger community.

The BRC adopted two national best practices: an intervention-based strategy for youth already inside the system and a prevention-based strategy to keep youth outside the system from entering it. The High Point Model, named for the North Carolina town where it was piloted, employs a focused deterrence approach with the involvement of several community actors to promote the success of the program.[87] In the High Point Model, the heads of several local street gangs, who are all on probation and are still at a point where they face the real prospect of rehabilitation, are called into a meeting. This focus group includes carefully screened young offenders who are told that they are heading down a path that, if left unchecked, will likely lead to a prison cell or the morgue. Examples are given of other people they know from the streets of our community who have already received heavy sentences or who have died as a result of criminal conduct.

State and federal law enforcement officers, probation officials, and members of my office tell these young offenders that life as they know it is over. Here forward, their actions, and those of their known associates, will be heavily monitored by a combination of a gang task force and probation officers. If the young offenders are arrested again, prosecutors will advocate for a high bond, pursue an indictment for being a habitual felon, and change the venue to federal court to maximize the time of active incarceration. My office has expanded its reach into the federal system by targeting gun crimes and drug offenses of violent gang members. Enforcing these laws is far more effective than prosecuting these defendants’ violent crimes in state court, where defendants fear the repercussions of being a snitch if they testify against other defendants from their neighborhoods.

The effectiveness of the High Point Model hinges not only on severe consequences but also on second chances. Participants are carefully screened by a team of police, prosecutors, probation officers, and judges to determine if they have the potential for rehabilitation through the program. To lend support to their success, participants are given a way to save face and to escape a life of crime through bimonthly call-in meetings. Present at the meeting are members of the young offender’s family, as well as pastors, educators, and other non-law enforcement representatives of the BRC. A member of our homicide support group is also present to share a testimonial about the effects that criminal activity has had on his family.

The young offenders are given the opportunity to continue their education by enrolling at the local community college to earn their GEDs or college credit. Members of the Wilmington Housing Authority YouthBuild U.S.A. Program[88] (a program, much like Habitat For Humanity, where at-risk youth are paid through a grant to build a home together) and a program called Leading Into New Communities (“LINC”)[89] (a group of ex-offenders who get reintegrated into society by working, at no cost to a potential employer, with grant money used to pay for the first four months of employment) are also on hand to offer employment. The message coming from the meetings is simple: everyone, from police to the offenders’ families, wants them to succeed and to avoid further contact with the criminal justice system. The choice of which path to travel can only be made by the young person listening.

The BRC also created a Youth Enrichment Zone (“YEZ”) patterned after the Harlem Children’s Zone.[90] The idea behind the YEZ was to look at crime statistics and hospital reports to identify the areas in our community needing the most help. After an exhaustive analysis of this data, we identified a fifteen-block area on the north side of Wilmington, the same area where McIver had been shot. The concept behind the YEZ is to start with a small geographic area and focus resources on the schools, houses of worship, businesses, and nonprofits that work directly with the young people living there. Young children, especially in the critical zero- to five-year-old population, are assessed to determine the resources necessary for their long-term success. Additional areas may be annexed in the future as success is demonstrated.

Many of the problems that we jointly confronted could better be addressed at the child’s house rather than at the courthouse or the schoolhouse. We hired a caseworker, a man who lives in the YEZ, to go door-to-door to make an assessment of resident needs and to do a de facto census of who was living at each residence. What he found was alarming, but not altogether surprising. He visited eighty-four homes and found that those homes were housing 231 school age children, ninety lived at or near the poverty line, 98.7% were African American, and only four fathers lived under the same roof as their children.[91]

We adopted the philosophy that, while resources would come from the outside, ultimately this needed to be an organic process where residents were made a part of the solution. We held town hall meetings to hear from residents about existing problems and current services to identify gaps and redundancies and to get the community to buy into the concept of the YEZ. We created a youth ambassador group, made up of young men and women in the YEZ, who went door-to-door with the caseworker. Instead of these young people joining gangs and becoming part of the problem, they are now setting a different example.

Recently, the middle school in the heart of the YEZ closed amid much controversy. The school, D.C. Virgo, was closed because it was historically underperforming, causing parents to pull their children out, reducing the number of students to only half the capacity.[92] The school board made the financial decision to close the school and bus the remaining students elsewhere. But to the children and parents within the YEZ, the school was a treasure, leading many to invoke the memory of the closing of Williston High School to say that history was repeating itself.[93]

The BRC moved quickly to try to remedy the problem. We recognized that our crime prevention efforts are ultimately tied to keeping the kids in school. We wrote a resolution requesting that the school board reopen D.C. Virgo within one year as either a magnet school within the public system or as a charter school. The school board listened and adopted the resolution.[94] Whether it ultimately takes the shape of a charter school or remains in the public system, it has already been determined that an advisory board, made up of community members, equally appointed by the BRC and school board, will help decide its future direction.

E. The Role of Law Schools in Community Prosecution

Recently at the annual bar meeting in Blowing Rock, North Carolina, Chief Justice Sarah Parker convened a meeting of the Executive Committee of the North Carolina Conference of District Attorneys and an even number of some of the leading members of the criminal defense bar. The meeting, moderated by Mel Wright, the executive director of the Chief Justice’s Commission on Professionalism, was called to see if the group could identify why there appeared to be so much animosity between the two sides and if there was any common ground that could begin to heal the divide. The resounding answer from both sides was that more needed to be done to train the new members of our profession.

Today, there are seven law schools in North Carolina turning out almost eleven hundred graduates each year, and an equal number sit for the Bar Exam. It is now largely believed that the supply of new lawyers has outstripped the demand for them. Today’s graduates enter a job market with few prospects, and many are forced to hang a shingle where mentoring is virtually nonexistent.

Both defense attorneys and prosecutors at the meeting concluded that prosecutors could do more to help train all attorneys in their communities. This is largely because jobs in public service, including prosecutors’ and public defenders’ offices, have continued to grow, while jobs in the private sector have largely dried up.[95] And the turnover in the offices suggests that the future is bright for new graduates to begin their legal careers in a district attorney’s office. Consider that there are more than six hundred prosecutors in North Carolina, and roughly half of them have been attorneys for less than five years.[96] The valuable mentoring that will take place in these offices will help shape the profession moving forward whether these young lawyers stay in public service for a lifetime or only a short while.

Following the Blowing Rock meeting, Mel Wright and I assembled a group of deans and professors from law schools across the state to meet at the Norman A. Wiggins School of Law at Campbell University. We pitched the idea of starting a public service class at the various schools where each dean would design a curriculum that fits students’ needs. Students would undertake a course work component that would include reading materials that are actually used in the field.[97] Professors could bring in guest lecturers who are prosecutors and public defenders in area districts. These professionals could start to be involved in the education of students while they are still students, rather than starting with on-the-job training as assistant district attorneys.

The training could continue with students working as externs at nearby district attorneys’ and public defenders’ offices during their fall and spring semesters. During the summer, they could continue their training in prosecutors’ and public defenders’ offices around the state. A website has been created by the Conference of District Attorneys to give students the opportunity to apply to offices in rural communities that are frequently overlooked by students and younger lawyers.[98] This structure will connect offices in need of new attorneys with students and recent graduates who are in need of a job.

Think of the benefits to our profession. Go to one of the seven law school campuses in North Carolina and you will find some type of “actual innocence” clinic.[99] These are worthy efforts and should continue. But we should remember that these clinics need balance for justice to be done in an adversarial system.[100] Respectfully, it is not the role of defense attorneys to “advocate for justice.” That job, including the responsibility of being first in line to see that innocents do not suffer, belongs to prosecutors.[101] Having prosecutors involved in these classes might not only sensitize future advocates to the crucial role of prosecutors, but it will allow for a greater dialogue on existing cases where actual innocence is alleged.[102] Giving students an opportunity to work directly with crime victims will also ensure that these law students are representing the actually innocent in the criminal justice system and upholding constitutional rights.[103]

As I mentioned earlier, prosecutors not only have the constitutional duty to advise law enforcement; they are given increasing responsibility in the training of officers on procedural and substantive law. It is better for our profession to focus some efforts on teaching our prosecutors to give officers good advice on the front end rather than focus all of our resources on assisting defense attorneys on suppression hearings and appeals later in the process. It is also unquestionably preferable to prevent wrongful convictions and constitutional violations at the trial level than attempt to undo these costly mistakes years later through endless appeals. These public service academics within law schools, in time, I believe, could include not only training for law students but could also serve as an academy for training assistant district attorneys and assistant public defenders.

Such a setting could also allow for more meetings between members of the criminal justice system to debate the great issues that confront us all. This Essay has explored just one large social issue, race and justice, to highlight how it can be addressed either through politics or through education. While the case method is effective in teaching the law,[104] it rarely serves the larger good to extrapolate from individual cases to set overall policies. Problems that appear to be ubiquitous, requiring dramatic overhaul to the system, are instead frequently episodic, confined to the case that receives all the attention.[105] These issues can continue to be debated by politicians with predicable outcomes or we can elevate the discussion by bringing defense attorneys and prosecutors together to begin to see if there is common ground. An academic setting provides the best possibility.

Finally, over time, an early emphasis on community prosecution might also begin to address the inadequate funding found in public service.[106] The gap between assistant district attorney pay and the pay for a beginning associate at a major firm left little cause for debate about the direction I would take right after graduation.[107] Today, students face an even larger and more crushing student debt load.[108] One long-term response to this issue is that law schools could begin to invest in the public service area of our profession. That can take the form of public interest grants for students working in district attorneys’ and public defenders’ offices during their summers and loan forgiveness for graduates who work in these offices after graduation. Although, with North Carolina Legal Education Assistance Foundation (“LEAF”) loan repayment money having recently been eliminated, the future is bleak.[109]