By: Dave Rugani*

Introduction

The advent of the limited liability company (“LLC”) in the 1980s has had far-reaching implications for how individuals choose to form business entities. Never before has there existed such a malleable legal entity that provides both limited liability and exemption from double taxation.[1] Indeed, since the passage of the first LLC act in 1977, all fifty states and the District of Columbia have followed suit.[2] The LLC is now viewed as the business entity of choice for small operations.[3] However, while the flexibility offered by an LLC is the source of great appeal for members, it has also posed unique challenges for courts that are, in many cases, deciding issues of first impression in the LLC context.

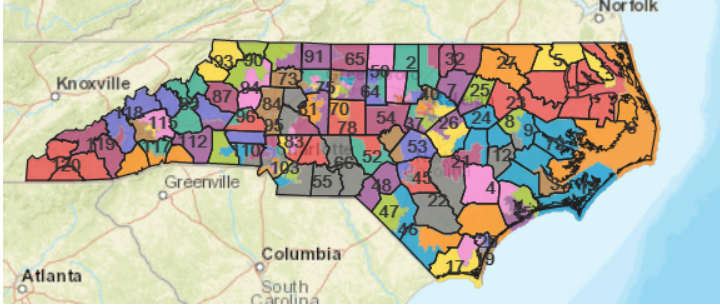

One especially vexing issue facing the courts is determining just how limited “limited liability” ought to be. In particular, courts are now determining whether, and to what extent, the equitable doctrine of veil piercing should be carried over from corporate law into the realm of the LLC. In North Carolina, like in many other states, LLC litigation has been slow to materialize, and the case law is sparse in comparison to the plethora of material on corporate or partnership law.[4] Nevertheless, it is now rather clear that North Carolina courts have followed every other state in permitting veil piercing in the LLC context, though they have failed to give special consideration to the peculiarities of the LLC, as have the courts of some other states. This Comment will consider the nature and scope of LLC veil piercing in North Carolina with a particular emphasis on its ineffective implementation and questionable application in certain contexts.

Part I of this Comment will provide background information that is necessary before considering the central issue. First it will examine the doctrine of corporate veil piercing and the general construction of the North Carolina Limited Liability Company Act’s (“LLC Act’s”) limited liability provision. This examination will be followed by a short survey of how states and commentators are beginning to treat LLC veil-piercing issues. Part II will discuss the case law in North Carolina regarding LLC veil piercing. This discussion will begin with a review of the leading case on corporate piercing in North Carolina, followed by a consideration of the LLC case law. Part III will critique the variety of factors the courts have used to pierce the veil, as well as the contexts in which the piercing has occurred. Of central importance is examining how the rationale for piercing in corporate contexts may, or may not, carry over to LLCs. This Comment will conclude with an argument that greater refinement of North Carolina case law is necessary in order to give effect to the equitable underpinnings of veil piercing in LLCs and to bring North Carolina law into accord with the emerging trends in other jurisdictions.

I. Background

As has often been observed, the LLC is a hybrid creature that adopts traits of both corporations and partnerships.[5] In order to encourage business formation, legislatures grafted onto the LLC two important characteristics. The limited liability provision of corporate law was combined with the pass-through taxation scheme from partnerships to create a unique business entity. These two features have made the LLC an irresistible option for many business incorporators. However, it is manifestly clear that providing absolute immunity from liability would be deleterious to the public good. The rationale underlying limited liability has always been to promote, or at least not punish, risk-taking behavior that is deemed vital to long-term economic prosperity.[6] Thus, limited liability provides a shield against the misfortunes of enterprise that are all too common in a competitive world. However, by not checking the reach of the statutory limited-liability provisions, the shield could become the sword of the unscrupulous.

A. Overview of Piercing the Corporate Veil

Recognizing this peril, courts long ago endeavored to find ways to protect the innocent. This response, piercing the corporate veil, provided the equitable check against abuse of the corporate form. Two observations about corporate veil piercing are in order. First, as an equitable remedy, it is purely a judicially created concoction without any basis in statutory law.[7] Second, “[t]here is a consensus that the whole area of limited liability, and conversely of piercing the corporate veil, is among the most confusing in corporate law.”[8]

A cursory overview of the doctrine of piercing the corporate veil is necessary before proceeding to a discussion of its application to LLCs. A leading treatise has observed:

[A]s a general rule, it is often said that the corporation will be viewed as a legal entity unless it is used to defeat public convenience or perpetrate or protect crime or fraud; when those situations occur, the courts will more carefully scrutinize the corporation and may regard it merely as an association of persons and extend liability to them.[9]

Therefore, a court may pierce the corporate veil—and subject the shareholder to personal liability—when there is both unity of interest such that no distinction exists between the corporation and the individual and when recognizing the corporate form would lead to injustice.[10] This unity of interest necessarily requires a showing that the corporation is the alter ego of the individual or the corporation is a mere instrumentality of the individual.[11] Almost always, this requires that a shareholder exercise domination or control over the corporation.[12]

The courts consider a litany of factors in determining what constitutes domination and control for the purposes of veil piercing, and these factors may change slightly from state to state. The principal factors include failure to observe corporate formalities, fraud, inadequate capitalization, illegality and evasion of a duty or obligation, sole shareholder corporations, loans to corporations, tortious or criminal conduct, commingling of assets, insolvency or bankruptcy, and failure to issue stock.[13] No factor is determinative, and the court must consider all of them holistically. Again, the factors are used to determine domination and control such that the corporation is but an alter ego of the shareholder. Moreover, absent an injustice, domination and control alone will never be enough to support a piercing claim.[14]

B. North Carolina’s Limited Liability Company Act

A detailed examination of the features of an LLC is beyond the scope of this Comment, as is assessing the relative value of using an LLC over other business entities. For the purpose of this Comment, it is sufficient to note that the limited liability characteristic of an LLC is one of the major benefits to members. North Carolina’s LLC Act[15] provides:

A person who is a member, manager, director, executive, or any combination thereof of a limited liability company is not liable for the obligations of a limited liability company solely by reason of being a member, manager, director, or executive and does not become so by participating, in whatever capacity, in the management or control of the business. A member, manager, director, or executive may, however, become personally liable by reason of that person’s own acts or conduct.[16]

This language is typical of other LLC statutes[17] that limit member liability “solely” on the basis of being a member. The law also contains a fairly common exception that members can be “personally liable by reason of that person’s own acts or conduct.”[18] It is on the basis of this language that the North Carolina courts have applied the corporate doctrine of veil piercing to the LLC.

At this juncture, it is useful to distinguish North Carolina’s limited liability provision from that of other states that specifically incorporate the doctrine of corporate veil piercing into the language of the statute. For example, both the Minnesota and Colorado statutes state that the court should use corporate veil piercing case law for determining individual member liability for LLCs.[19] Most states, including North Carolina, do not have such unequivocal statutory language, and it has fallen to the courts to pick up where the legislatures have left off. As previously noted, North Carolina has joined every other state in transferring the veil-piercing doctrine from the corporate to the LLC setting.

C. How Other States Treat LLC Veil Piercing

North Carolina is certainly not the first state to face the challenge of defining the contours of piercing the liability shield, and a cursory assessment of the views of other jurisdictions is helpful in understanding North Carolina’s current status. In the birthplace of the LLC, the Supreme Court of Wyoming addressed the piercing issue in Kaycee Land & Livestock v. Flahive,[20] where the court held that, though piercing should be permitted, the factors considered would likely differ from factors used in the corporate setting.[21] In particular, failing to follow formalities would be a poorly-suited factor in the LLC context, given how few formalities are required by statute.[22] This view has been shared by numerous other legislatures and courts.[23] Indeed, section 304(b) of the Uniform Limited Liability Act specifically provides that “[t]he failure of a limited liability company to observe the usual company formalities or requirements . . . is not a ground for imposing personal liability on the members or managers for liabilities of the company.”[24] At least one court has opined that, while the same factors apply to both corporations and LLCs, the factors should be balanced differently.[25]

Another suspect factor seems to be whether domination and control of the LLC by its members should be considered. This is because most LLC statutes, by their plain terms, specifically allow for a flexible approach to governance. For example, members may be managers and authorized agents of the LLC—greatly blurring the line between management and ownership.[26] A treatise on the subject notes that there seems to be a “legislative intent to allow small, one-person and family-owned businesses the freedom to operate their companies themselves and still enjoy freedom from personal liability.”[27] One commentator has observed that in a member-managed LLC, the member is akin to a corporate shareholder who is also a director.[28] Just as these shareholders are the most likely targets for a piercing claim in the corporate setting, member-managers have increased exposure.[29] This would seem a curious result in an LLC. As one court noted, “Lesser weight should be afforded the element of domination and control . . . because the statute authorizing limited liability companies expressly authorizes managers and members to operate the firm.”[30]

A third factor that is of questionable application to LLC piercing is inadequate capitalization. Most LLC acts provide for a statutory remedy for creditors who are injured due to the LLC’s inadequate capitalization,[31] thus making undercapitalization as a piercing factor redundant.[32] Others have taken a more restrained approach, with one court stating that “[u]ndercapitalization is another factor that should be weighed carefully in the L.L.C. context . . . .”[33]

Thus, the prevailing trend seems to be that an LLC should be pierced, but the factors to be considered may require modification from the corporate model.[34] Nevertheless, there is still a significant body of law that has applied corporate veil-piercing factors to LLCs without modification.[35] One commentator has gone so far as to suggest that piercing should not be permitted in the LLC context, though no court has adopted that view.[36] Against this general backdrop the North Carolina law will now be examined.

II. North Carolina Case Law

Turning to North Carolina, it is clear that LLC veil piercing is ongoing. It is equally evident that the case law can be broadly divided into two groups: (1) cases that pierce while citing to section 57C-3-30 of the LLC Act[37] and (2) cases that pierce without referring to the statute. Before considering either group, it will be beneficial to examine the leading corporate piercing case, as that provides the basis for piercing in the latter group of cases.

A. Corporate Veil Piercing in North Carolina: The Instrumentality Rule of Glenn v. Wagner

North Carolina courts have long given effect to veil piercing in the corporate setting. Though veil piercing has been recognized in North Carolina since 1899,[38] the leading case is Glenn v. Wagner.[39] The Supreme Court of North Carolina explained the “instrumentality rule”[40] as “[a] corporation which exercises actual control over another, operating the latter as a mere instrumentality or tool, is liable for the torts of the corporation thus controlled. In such instances, the separate identities of parent and subsidiary or affiliated corporations may be disregarded.”[41] The three elements necessary to prevail under the instrumentality rule are:

Control, not mere majority of complete stock control, but complete domination, not only of finances, but of policy and business practice in respect to the transaction attached so that the corporate entity as to this transaction had at the time no separate mind, will or existence of its own; and

Such control must have been used by the defendant to commit fraud or wrong, to perpetrate the violation of a statutory or other positive legal duty, or a dishonest and unjust act in contravention of plaintiff’s legal rights; and

The aforesaid control and breach of duty must proximately cause the injury or unjust loss complained of.[42]

Thus, in North Carolina, control and domination form the critical matter necessary to prevail on a piercing theory.

The court then went on to discuss the factors that are “considered inherent in the instrumentality rule.”[43] These include inadequate capitalization, failure to follow corporate formalities, complete domination and control such that no independent identity exists, excessive fragmentation of an enterprise, nonpayment of dividends, insolvency of the debtor corporation, siphoning of funds, and the nonfunctioning of officers and directors.[44] These factors are used to determine the first prong of the instrumentality test.[45]

The Glenn test has been applied in numerous contexts. In the case itself, the instrumentality rule was used to pierce under a so-called enterprise theory.[46] At issue were two corporations, one the parent and the other a subsidiary.[47] The parent’s domination and control of the subsidiary, combined with unjust conduct, was enough to permit a piercing.[48] In addition, Glenn has been used in the more traditional setting of allowing a third party to sue the individual shareholder of a corporation.[49] Finally, courts have used Glenn to justify so-called reverse piercings whereby the third parties—usually creditors of the shareholder-debtor—are allowed to recover against the corporation of which the debtor is a shareholder.[50] The question then becomes whether, and to what extent, Glenn and the subsequent case law on corporate piercings are relevant to LLC piercing. As already noted, the case law is split between piercing claims that cite to the statute and those that cite to Glenn.

B. Cases that Cite to Section 57C-3-30

It is less than ideal that the only North Carolina Supreme Court opinion on the issue is also one of the least helpful. In Hamby v. Profile Products, L.L.C.,[51] the plaintiff was a purported tort victim who brought an action against his employer, Terra-Mulch Products, L.L.C., and Terra-Mulch’s sole member and manager, Profile Products, L.L.C.[52] The complaint alleged that Profile “dominate[d] and control[ed] Defendant Terra-Mulch and [was] the alter ego of Defendant Terra-Mulch.”[53] The court went on to state that “when a member-manager acts in its managerial capacity, it acts for the LLC, and the obligations incurred while acting in that capacity are those of the LLC.”[54] Frustratingly, the court did not take the opportunity to examine the various piercing factors. Instead, it merely held that Profile’s exercise of managerial control over Terra-Mulch, on its own, was not enough to subject Profile to liability.[55]

Hamby leaves much to be desired. First, it merely states the obvious: member-managers cannot be held liable based purely on their exercise of managerial powers.[56] Second, the court did not bother to dwell on what factors would be considered in a viable piercing situation. Third, the court did not engage in a thorough analysis of the statute and how it contrasts with relevant corporate liability provisions.

In State ex rel. Cooper v. NCCS Loans, Inc.,[57] a case that preceded the Hamby decision, the North Carolina Court of Appeals provided a more substantial consideration of section 57C-3-30. At issue there was an LLC that provided small loans to customers at rates in flagrant disregard of the state’s usury laws as well as numerous consumer protection statutes.[58] In permitting the defendant-member to be held personally liable, the court concluded that “Section 57C-3-30(a) clearly anticipates that a member who is also a ‘manager, director, executive, or any combination thereof’ might be made a defendant and ‘become personally liable by reason of [his] own acts or conduct.’”[59] The court emphasized the word “solely” in the text of the statute as providing a basis for this view.[60]

The court then elaborated on two factors that supported its conclusion that the member should be individually liable. First, he “entirely owned and controlled” the company.[61] Second, he used his position as a member to direct unlawful practices and create a number of shell organizations in a deliberate attempt to avoid liability.[62] While seemingly rational, holding a member individually liable raises two issues. First, how does complete ownership and control make sense as a piercing consideration in the wake of Hamby?[63] Second, the court seems to be alluding to inequitable conduct as being a major consideration for piercing; does that mean the court is, at least implicitly, applying the second prong of the instrumentality test articulated in Glenn?[64]

The cases that have cited to section 57C-3-30 are few, and their holdings are unremarkable. Section 57C-3-30 does not confer absolute immunity, and the courts will pierce the veil when justice so requires. The finer details of piercing are left undiscussed, and there is no mention of the Glenn test.

C. Cases that Apply Glenn to Piercing an LLC

Notwithstanding the lack of direction emanating from the Hamby opinion, North Carolina courts have pierced LLCs with zeal. This is hardly surprising, as every other jurisdiction has done just that.[65] What is truly remarkable is that the courts are disregarding limited liability without even mentioning section 57C-3-30. In all of the following cases, the courts have allowed the plaintiff to pierce the liability shield on the basis of the corporate piercing factors discussed in Glenn.

Perhaps the most instructive case on the matter is the North Carolina Supreme Court’s decision in State ex rel. Cooper v. Ridgeway Brands Manufacturing, LLC.[66] There, Ridgeway Brands Manufacturing, LLC was owned by member-manager James Heflin.[67] The company produced tobacco and sold it to Ridgeway Brands, Inc., which was owned and managed by Fred Edwards and Carl White.[68] Ridgeway Brands Manufacturing, LLC sold most of its products to the corporation.[69] The problem was that, beginning in 2003, Ridgeway Manufacturing, LLC did not maintain a qualified escrow account as required by statute for cigarette producers.[70] At the same time, Ridgeway Brands Manufacturing, LLC sold its products to the corporation at a cut rate.[71] The result was that the corporation experienced disproportionately high revenue compared to its competitors, and Ridgeway Brands Manufacturing, LLC did not have enough money to pay into the mandatory escrow account.[72] At some point in 2003, both the corporation and the LLC entered into a merger; corporate formalities were not observed, but the merger became de facto.[73]

The court began by restating the adage that the corporate form will be disregarded when it is used to “shield criminal wrongdoing, defeat the public interest, and circumvent public policy.”[74] Next, the court reviewed the instrumentality rule from Glenn and applied it to the case at bar.[75] Notably, the court did not distinguish between a corporation and an LLC. The piercing factors cited by the court included directing money to individuals instead of the company, excessively fragmenting the company, destroying “corporate”[76] documents, and directing the movement of funds so as to avoid statutory obligations.[77] Ultimately, the plaintiff was allowed to pierce the veil.

Ridgeway is a very difficult case to analyze. The crux of the problem is that the court did not state, and it is by no means clear, whether the plaintiff was piercing an LLC or a corporation. Both Ridgeway Brands Manufacturing, LLC and Ridgeway Brands, Inc. were named as defendants (along with Heflin, Edwards and White), yet at some point the LLC and the corporation had merged, albeit without observing the statutory strictures for a proper merger. Throughout the opinion, the court specifically distinguished between “Ridgeway” the LLC, and “Brands” the corporation, but it made clear that the two combined at some point in 2003.[78] Did the court permit the plaintiff to pierce the veil of the LLC, the corporation, both, or the combined entity that resulted from the merger?[79]

Three possible conclusions may be drawn from Ridgeway. First, the entity in question was actually a corporation, and thus the application of Glenn was perfectly logical. Second, the entity was an LLC, and the court intended to apply Glenn to LLCs without modification. Third, the entity was an LLC, but the court failed to consider the differences between the corporate form and an LLC. The first and third propositions are certainly plausible and would go a long way toward alleviating the confusion. The second proposition seems difficult to accept; did the court really intend to allow piercing on the basis of, for example, failing to adhere to corporate formalities?[80]

What is left, then, is a series of lower court decisions that have applied the Glenn factors to LLCs without ever discussing the specific LLC context or section 57C-3-30. For example, in Anderson v. Dobson,[81] the United States District Court for the Western District of North Carolina quoted the instrumentality test from Glennverbatim and then applied the four factors necessary to show control: inadequate capitalization, failure to follow corporate formalities, lack of an independent identity, and excessive fragmentation.[82] The court concluded that having no assets, employees, or stock and having one person fill the position of officer, director, and registered agent was not enough to establish control within the meaning of Glenn.[83]

An illustrative case is Bear Hollow, L.L.C. v. Moberk, L.L.C.,[84] decided by the same district court. At issue there was the sale of real estate from the defendant-LLC to the plaintiff.[85] The plaintiff was induced to complete the sale on the advice of his confidant and agent.[86] Unbeknownst to the plaintiff, his agent was actually in the employ of the defendant.[87] After the completion of the sale, the plaintiff learned of his agent’s conduct and of the unfair price at which he purchased the land.[88] The plaintiff’s suit included nine causes of action, including fraud and conspiracy, and sought to pierce the veil of the LLC.[89]

In permitting the veil-piercing theory to go forward,[90] the court immediately cited to Glenn and its three-part test and went on to recite all of the corporate factors that are considered in a piercing claim.[91] Ultimately, the court found the plaintiff’s allegation to be sufficient to withstand dismissal, namely because the defendant-LLC “was inadequately capitalized, failed to comply with corporate formalities, and was completely dominated and controlled by [the two individual members] such that it has no separate mind, will or existence of its own . . . .”[92]

Though decided on a motion to dismiss, the court’s position is still rather remarkable. The three factors cited by the court—inadequate capitalization, failure to comply with formalities, and complete domination and control—are precisely the three factors that have questionable application to LLCs.[93]

Another particularly vexing problem arises when the courts exclaim that LLC veil piercing is clearly permitted under North Carolina case law and then go on to cite to purely corporate authority for support. Such was the case in White v. Collins Building, Inc.,[94] where the North Carolina Court of Appeals stated, “It is well settled that an individual member of a limited liability company or an officer of a corporation may be individually liable for his or her own torts, including negligence.”[95] The court then cited to five cases that all involved corporations, not LLCs.[96]

Similarly, the court in L’Heureux Enterprises, Inc. v. Port City Java, Inc.[97] stated, “It is well established that in certain circumstances North Carolina will disregard the separate and independent existence of a corporation or limited liability company to hold a shareholder or member liable[.]”[98] The court then cited to American Jurisprudence[99] for support;[100] the cited material does not contain even a single reference to LLCs. After considering the “well-established” situations in which piercing is permitted, the court applied Glenn and denied the plaintiff’s piercing claim.[101]

In a slightly different setting, the courts are equally muddled about the application of piercing factors in a reverse pierce situation. For example, in In re AmerLink, Ltd.,[102] the bankruptcy court allowed the plaintiff to pierce through the LLC to reach the assets of the individual member. What transpired was a myriad of transactions between numerous corporations and LLCs all owned and controlled by the same person.[103] These transactions had the effect of removing assets from the various entities and enriching the individual defendant to the detriment of creditors.[104] At the outset, the court, citing Strategic Outsourcing, Inc. v. Stacks,[105] noted that “North Carolina law also recognizes ‘reverse piercing,’ where one entity is the alter ego of another entity, shareholder, or officer, so that the two entities may be treated like one-in-the-same.”[106] In applying Glenn, the court found that the individual member had “complete control”[107] over AmerLink and used this control to force AmerLink into a series of transactions in “furtherance of wrongs and breaches of duty . . . .”[108]

North Carolina law is thus split along an axis whereby some courts cite to the statute and others to Glenn. In no case has any court engaged in a meaningful discussion about tailoring piercing claims to an LLC.

III. Analysis of North Carolina Case Law as Applied to Limited Liability Companies

A synthesis of North Carolina law is in order. Glenn establishes the instrumentality test for piercing the corporate veil. Among the many factors listed by the court, four are especially probative: inadequate capitalization, noncompliance with corporate formalities, complete domination and control of the corporation so that it has no independent identity, and excessive fragmentation.[109] In applying these factors, the central consideration is whether the shareholder exercised such complete domination over the corporation that it had no separate existence, and such domination resulted in inequitable conduct.[110]

Cases that interpret section 57C-3-30 provide few details as to how courts should pierce the veil of an LLC. Only two things can be determined for certain. First, as should be obvious from reading the statute, the liability shield provided to an LLC is not absolute under North Carolina law and can be disregarded under certain conditions. For example, courts have held members liable on at least two occasions where the members used the LLC to violate positive statutory law.[111] Second, a member can be held liable if he assumes an independent duty separate and apart from that of the company.[112] No court has engaged in an analysis of the relevant piercing factors under section 57C-3-30.

Numerous courts have allowed a plaintiff to pierce the veil of an LLC without considering section 57C-3-30. These courts have generally applied the instrumentality test articulated in Glenn, as well as the corporate piercing factors considered therein. In applying Glenn to LLCs, courts have considered inadequate capitalization,[113] complete and total control of the company,[114] failure to follow corporate formalities,[115] excessive fragmentation, and siphoning of funds.[116] No court has assessed whether these corporate factors are appropriate in the LLC setting. Similarly, no court has examined the interplay between Glenn and section 57C-3-30.

It would be a fair assessment to say that the courts have thus far failed to view an LCC as fundamentally different from a corporation, notwithstanding their many similar traits. It is folly to suggest, as the North Carolina courts have implied, that all factors relevant to a corporate piercing analysis should be imported to a discussion on LLC piercing. When the North Carolina General Assembly passed the Limited Liability Company Act, it created an entity that is different in kind, and not merely degree, from a corporation. The LLC in North Carolina, like everywhere else, essentially combines the limited liability of a corporation with the flexibility of a partnership. The result is a highly flexible entity that is not burdened by the confines of corporate formalism and procedure. The rationale for creating such an entity, and the wisdom in doing so, is not relevant to a court’s analysis. It is sufficient that the General Assembly has created such an entity, and the courts must tailor their holdings to give effect to the peculiar traits of the LLC. The applicability of the various Glenn factors will now be considered in turn.

A. Inadequate Capitalization

It is not difficult to see why courts are concerned with a business entity being deliberately undercapitalized: it allows the individual to engage in nefarious conduct without meaningful consequence.[117] If courts did not consider this, an individual could engage in any sort of behavior, and the plaintiff’s relief would be limited to the corporate coffers that were deliberately left bare in anticipation of just such an event. An alternative conceptualization is that limited liability is a privilege created by the legislature, and as a privilege, it should not be abused.[118]

Of particular relevance to the question of undercapitalization is section 57C-4-06 of the North Carolina LLC Act,[119] which provides that an LLC may not make a distribution if doing so would render the company unable to satisfy its debts as they come due or would make assets less than the sum of liabilities and preferential rights of members if dissolution resulted.[120] The statute then goes on to impose personal liability on any member who votes for a distribution that would violate section 57C-4-06.[121]

As mentioned previously, commentators and courts are divided about whether undercapitalization is a relevant factor for piercing the veil of an LLC.[122] Nevertheless, this statutory section provides a strong justification for not extending that factor to LLCs in North Carolina. There is simply no reason to rely on an equitable remedy when there is a statutory remedy for the same wrong. Veil piercing was created by the courts to prevent the unscrupulous from using the corporate form to abuse innocent third parties. This justification for piercing, with respect to inadequate capitalization, is greatly undermined when the legislature has set forth its own form of relief.

That said, there are issues that need mentioning. First, no North Carolina court has given careful consideration to section 57C-4-06. This raises the spectacle that a court might constrain the language of the statute to provide a lesser remedy than would be the case in a traditional veil-piercing claim. Second, and more importantly, section 57C-4-06(a) seems to only provide protection to contract creditors, as opposed to tort victims. The case history is rife with examples of individuals abusing limited liability to the detriment of a third party.[123] Thus, inadequate capitalization may be a valid factor in certain cases but not others.

B. Domination and Control by an Individual

In the corporate setting, complete control and domination can occur in two situations. The first is the case of a dominant shareholder, while the second is the parent-subsidiary relationship.[124] In either case, the rationale for imposing liability is that the dominant party has disregarded the statutorily required degree of separation from the controlled corporation.[125] This problem is especially acute when there is a very small number of shareholders who may also occupy a management position. An empirical study by Professor Robert Thompson is particularly illuminating.[126] His survey of 297 cases indicated that when the defendant was both a shareholder and a manager, the court pierced the corporate veil in 46.46% of the cases.[127] Further, the same data revealed that in 186 of those 297 cases there were three or fewer shareholders in total.[128] Thus, courts are more likely to pierce when the shareholder is also an active manager and when there are few shareholders.

For LLCs, the LLC Act specifies that “[o]ne or more persons may form an LLC . . . .”[129] Moreover, the organization of an LLC “requires one or more initial members and any further action as may be determined by the initial member or members.”[130] The LLC Act also provides that, by default, all members are managers.[131] It seems clear that the LLC Act allows a single individual to own an LLC completely and to simultaneously exercise full control over its management.

On the one hand, it is seemingly logical that an LLC completely controlled by a single member is exactly the sort that is likely to have no separate existence apart from the member and harm third parties. On the other hand, the statutory language is unequivocal in permitting a single individual to control an LLC.[132] This distinction cannot be overstated. A corporation, almost by definition, separates ownership from management. The active investor is the exception, not the rule. LLCs do away with this and instead allow a single individual to not only own the enterprise completely but also exert full managerial control.

C. Excessive Fragmentation

Of particular concern for corporate creditors is the possibility that incorporators will divide the business into multiple entities that serve no useful business purpose but rather are created so as to frustrate creditors’ recovery.[133] Using multiple corporations creates the specter of lengthy litigation for creditors and thus higher costs. An individual might, for example, create two corporations in connection with a single business activity. One corporation would contain the assets, while the other would be saddled with the liabilities. A creditor of the liability corporation would have no recovery because the assets have all been segregated into the asset corporation. To avoid this result, North Carolina courts consider fragmentation when confronted with a piercing claim.

The LLC Act provides no direction as to how courts should apply this factor to an LLC. However, it is reasonable that the same concern present in the corporate realm exists with LLCs. In order to protect creditors against inequitable results, it must surely be the case that the courts must consider excessive fragmentation.

D. Failure to Observe Corporate Formalities

Corporate formalities, at least in theory, serve a variety of purposes. For example, by maintaining segregation of corporate and personal assets, third parties can have greater confidence that they are contracting with the corporation and not the individual.[134] Formalities may also protect shareholders from insider malfeasance.[135] For example, by requiring a corporation to keep records of its dealings and minutes of its board meetings, a disgruntled shareholder has a basis for evaluating the directors’ performance. This documentation will also be critical if the dispute results in litigation. One commentator put the rationale more directly: if owners do not treat the corporation as a separate entity, why should the courts?[136]

Like most LLC statutes, North Carolina’s imposes very few formalities. One is that the LLC file with the Secretary of State articles of organization that include the name of the company, life of the entity, address of each person executing the articles, address of the registered office, and address of the principal office, if any.[137] Another requirement is that the company file with the Secretary of State an annual report, which must contain substantially the same information as the articles of organization, except the annual report must also include a “brief description of the nature of [the] business.”[138] A third requirement is that the company maintain a registered agent and office that is subject to service.[139] These few formalities aside, the statute provides great flexibility for members to operate free and clear of statutorily imposed procedures.

Commentators have almost universally maligned the transplant of this factor from the corporate world to the LLC.[140] In the first instance, LLC statutes, including North Carolina’s, lack the formalism of corporate statutes.[141] A more practical concern is that LLCs are likely to be small and closely held and thus unlikely to focus on formalities that do not affect the business operation.[142] Moreover, by imposing corporate formalities on LLCs, courts would be frustrating the intent of the legislature to provide a flexible form of business organization.[143] Given the paucity of formalities required by the General Assembly, it would seem unreasonable for North Carolina courts to impose them and thus run afoul of the clear will of the legislature.

A rigid application of Glenn would seem to be at odds with the statutory scheme of the LLC Act, and therefore the courts must endeavor to formulate a more appropriate test. This is not to say that the central holding of Glenn is wrong; it is almost certainly correct. Business entities should not be permitted to abuse their existence to the detriment of third parties. The potential for using an LLC to circumvent public policy is just as great as with a corporation. What is needed is a tailored approach for LLCs that acknowledges that not all factors relevant to a corporate piercing should be applied to an LLC.

Conclusion

An influential article on the subject once analogized piercing to lightning: it is rare, severe, and unprincipled.[144] In order to ameliorate the tempest (at least with respect to LLC piercing), courts must be cognizant of three realities. First, the legislature clearly did not intend to confer absolutely limited liability. Second, the General Assembly has implicitly agreed with the notion of veil piercing in the LLC context. The General Assembly could have prevented the use of the equitable remedy but chose not to do so, thus granting at least tacit approval for the practice. Third, an LLC is not a rehashed corporation; it is a fundamentally different creation. It has its own parlance, statute, forms, requirements, and procedures. It is only natural that it needs its own independent body of law.

Accordingly, North Carolina courts should place special emphasis on the second element of the Glenn test—whether there was fraud, a violation of a statutory duty, or unjust conduct.[145] This is, after all, what the legislature wanted to avoid in only providing limited (as opposed to absolute) limited liability. The first part of the instrumentality test—control and domination such that there is no independent existence—should not be stressed to the same extent.

In evaluating this first prong, the factors need to be reconsidered in application to an LLC. First, the failure to observe formalities should not be relevant given that the statute requires so few. Second, allowing a plaintiff to pierce because a single individual completely owns and controls the company would seem odd in light of a statute that permits precisely that. Lack of adequate capitalization is a more difficult question, but in light of section 57C-4-06 it would make sense to reevaluate its application. In particular, lack of adequate capitalization should not be a factor in contract piercing actions but should remain a consideration for tort victims who might not have a statutorily created remedy. Fragmentation of the company into any number of meaningless shells remains a concern, and the courts should be on guard.

It might well be the case that piercing factors become increasingly irrelevant, with the great emphasis being the second element of the test. Indeed, this may already be the case. In both Gunnings and NCCS Loans, the piercing was predicated, in large part, on the defendants’ gross violations of consumer protection acts and usury laws, with no treatment of the piercing factors.

Refining, or at least rebalancing, the piercing factors for LLCs would harmonize North Carolina’s law with that of several other states, including Wyoming, Minnesota, Colorado, and California.[146] Other state courts may be moving in a similar direction, as evidenced by the courts’ thoughtful discussions in both In re Giampietro[147] (Nevada) and D.R. Horton[148] (New Jersey).

It seems clear that lower courts are going to continue to decide LLC veil-piercing issues in a haphazard manner unless and until the North Carolina Supreme Court revisits the issue in more a thorough way than it did in Hamby. What is needed is a tailored approach to LLCs that recognizes their uniqueness and distinctiveness from corporations. By reconsidering piercing factors in light of the LLC Act and the General Assembly’s intent in creating LLCs, a more sound principle of equity will be achieved to the benefit of all.

[1]. See generally Larry E. Ribstein & Robert R. Keatinge, Ribstein and Keatinge on Limited Liability Companies § 1:2 (2d ed. 2011).

[3]. See David L. Cohen, Theories of the Corporation and the Limited Liability Company: How Should Courts and Legislatures Articulate Rules for Piercing the Veil, Fiduciary Responsibility and Securities Regulation for the Limited Liability Company?, 51 Okla. L. Rev. 427, 429 (1998) (discussing the significance of the LLC in Delaware).

[4]. See William Meade Fletcher, Fletcher Cyclopedia of the Law of Corporations § 18 (2012).

[5]. Russell M. Robinson, II, Robinson on North Carolina Corporate Law § 34.01 (7th ed. 2006) (noting that an LLC “combines characteristics of business corporations and partnerships”); Geoffrey Christopher Rapp, Preserving LLC Veil Piercing: A Response to Bainbridge, 31 J. Corp. L. 1063, 1066 (2006) (“An LLC is frequently described as a ‘hybrid’ entity . . . .”).

[6]. For example, Judge Easterbrook and Professor Fischel argue that, in the corporate setting, limited liability provides six key benefits: it decreases the need to monitor, reduces the cost of monitoring, incentivizes manager efficiency, allows for the impounding of additional information about the value of the firm, allows for efficient diversification, and facilitates optimal investment decisions. Frank H. Easterbrook & Daniel R. Fischel, Limited Liability and the Corporation, 52 U. Chi. L. Rev. 89, 94–97 (1985).

[7]. This is true in the corporate context. Some LLC statutes, however, specifically incorporate veil piercing. See infra note 18.

[8]. Easterbrook & Fischel, supra note 6, at 89.

[9]. Fletcher, supra note 4, § 41.

[13]. Id. §§ 41.30, 41.34. For a detailed discussion of each of these factors, see id. §§ 41.31–.60.

[15]. North Carolina Limited Liability Company Act, N.C. Gen. Stat. § 57C (2011).

[17]. Professor Karin Schwindt groups North Carolina’s statute with Alaska, Kentucky, Mississippi, Missouri, Nebraska, New Hampshire, New Jersey, New York, Ohio, Oregon, South Carolina, and Washington, D.C. Karin Schwindt, Limited Liability Companies: Issues in Member Liability, 44 UCLA L. Rev. 1541, 1554 n.60 (1997).

[18]. N.C. Gen. Stat. § 57C-3-30.

[19]. Colo. Rev. Stat. § 7-80-107 (2011); Minn. Stat. § 322B.303(2) (2012); see also Jeffrey K. Vandervoort, Piercing the Veil of Limited Liability Companies: The Need for a Better Standard, 3 DePaul Bus. & Com. L.J. 51, 65 (2004) (discussing the various treatments that statutes give to the existing body of corporate veil-piercing case law with respect to LLCs).

[20]. 46 P.3d 323 (Wyo. 2002).

[21]. The court stated:

Certainly, the various factors which would justify piercing an LLC veil would not be identical to the corporate situation for the obvious reason that many of the organizational formalities applicable to corporations do not apply to LLCs. The LLC’s operation is intended to be much more flexible than a corporation’s. Factors relevant to determining when to pierce the corporate veil have developed over time in a multitude of cases.

Id. at 328.

[23]. See, e.g., Cal. Corp. Code. § 17101(b) (West 2012) (stating that failure to follow formalities is not a ground for imposing individual liability); D.R. Horton Inc.–New Jersey v. Dynastar Dev., L.L.C., No. MER-L-1808-00, 2005 WL 1939778, at *36 (N.J. Super. Ct. Law Div. Aug. 10, 2005) (“It is sufficient for this court to conclude that in this case, [the defendant’s] failure to scrupulously identify the entity through which he was acting . . . should not loom as large as it might were the entity a corporation.”).

[24]. Revised Unif. Ltd. Liab. Co. Act § 304(b) (2006).

[25]. In re Giampietro, 317 B.R. 841, 848 n.10 (Bankr. D. Nev. 2004) (“It may very well be that while the same principles used in corporate alter ego cases may apply to limited liability companies, they may apply with different weight.”).

[26]. Vandervoort, supra note 19, at 70 (“[G]enerally speaking, members are normally authorized agents and/or managers of LLC’s for the purpose of conducting its affairs.”).

[27]. Stephen B. Presser, Piercing the Corporate Veil § 4:2 (2011).

[28]. Schwindt, supra note 17, at 1559.

[30]. D.R. Horton Inc.–New Jersey v. Dynastar Dev., L.L.C., No. MER-L-1808-00, 2005 WL 1939778, at *31 (N.J. Super. Ct. Law Div. Aug. 10, 2005).

[31]. Ribstein & Keatinge, supra note 1, § 12:3.

[32]. Cf. Vandervoort, supra note 19, at 72 (“[U]ndercapitalization appears to be directly applicable to LLC’s with little or no modification.”).

[33]. D.R. Horton Inc., 2005 WL 1939778, at *36.

[34]. See, e.g., In re Giampietro, 317 B.R. 841, 848 n.10 (Bankr. D. Nev. 2004) (“It may very well be that while the same principles used in corporate alter ego cases may apply to limited liability companies, they may apply with different weight.”); Kaycee Land & Livestock v. Flahive, 46 P.3d 323, 328 (Wyo. 2002)(“Certainly, the various factors which would justify piercing an LLC veil would not be identical to the corporate situation . . . .”).

[35]. See In re Giampietro, 317 B.R. at 847 n.9 (citing various cases that treat veil piercing the same in both the LLC and corporate context).

[36]. Stephen M. Bainbridge, Abolishing LLC Veil Piercing, 2005 U. Ill. L. Rev. 77, 79 (2005).

[37]. See supra note 16 and accompanying text.

[38]. Robinson, supra note 5, § 2.10.

[39]. 329 S.E.2d 326 (N.C. 1985).

[41]. Id. (quoting B-W Acceptance Corp. v. Spencer, 149 S.E.2d 570, 575 (N.C. 1966)).

[49]. See, e.g., L’Heureux Enter., Inc. v. Port City Java, Inc., No. 06 CVS 3367, 2009 WL 4644629, at *8–9 (N.C. Super. Ct. Sept. 4, 2009).

[50]. See, e.g., In re AmerLink, Ltd., No. 09-01055-8-JRL, 2011 WL 874140, at *3 (Bankr. E.D.N.C. Mar. 11, 2011).

[51]. 652 S.E.2d 231 (N.C. 2007).

[54]. Id. at 236. The Hamby court was applying the law of Delaware, but the analysis would be the same for North Carolina. Importantly, the court stated:

North Carolina’s third-party liability statute, N.C.G.S. § 57C-3-30(a), is substantially similar to that of Delaware, Del.Code Ann. tit. 6, § 18-303(a). Both statutes state that members or managers cannot be held liable for the obligations of an LLC “solely by reason of” being members or managers or participating in management of an LLC. Del.Code Ann. tit. 6, § 18-303(a); N.C.G.S. § 57C-3-30(a). The North Carolina statute also states that members or managers may be held personally liable for their “own acts or conduct.” See N.C.G.S. § 57C-3-30(a). However, this language appears to simply clarify the earlier principle: the liability of members or managers is not limited when they act outside the scope of managing the LLC.

Id. at 236 n.1.

[55]. Id. at 236; see also Spaulding v. Honeywell Int’l, Inc., 646 S.E.2d 645, 649 (N.C. Ct. App. 2007) (“[I]n the absence of an independent duty, mere participation in the business affairs of a limited liability company by a member is insufficient, standing alone and without a showing of some additional affirmative conduct, to hold the member independently liable for harm caused by the LLC.”). The failure of a member to investigate a fellow member for malfeasance is insufficient, absent actual knowledge of the malfeasance, to establish personal liability under section 57C-3-30. Babb v. Bynum & Murphrey, PLLC, 643 S.E.2d 55, 57 (N.C. Ct. App. 2007).

[56]. In an earlier case it was held that it was improper under Rule 11 of the North Carolina Rules of Civil Procedure to name a member of an LLC as a defendant in an action against the LLC without any evidence to support the claim. Page v. Roscoe, L.L.C., 497 S.E.2d 422, 428 (N.C. Ct. App. 1998). This case, the first to reference section 57C-3-30, arguably was the first to open the door to an LLC piercing claim because it seemingly limited the holding to instances where there is no evidence to support an individual claim. It is implicit that, had there been appropriate evidence, the outcome would have been different.

[57]. 624 S.E.2d 371 (N.C. Ct. App. 2005).

[60]. Id. at 379. In a later case brought in federal court, the court, in applying the test from NCCS Loans, held that individual liability would attach to members who exerted control over the companies and who were “directly and personally involved in the fraudulent scheme.” Gunnings v. Internet Cash Enter. of Asheville, No. 5:06CV98, 2007 WL 1931291, at *6 (W.D.N.C. July 2, 2007). This court also noted that ownership of the LLC is enough; the defendant-member does not need to control the day-to-day operations to be held liable. Id.

[61]. NCCS Loans, 624 S.E.2d at 380.

[63]. Recall that the Hamby court did not think complete ownership and control was relevant in the LLC context because the statute clearly allowed member-managers to control the LLC. Hamby v. Profile Prods., L.L.C., 652 S.E.2d 231, 236 (N.C. 2007).

[64]. The NCCS Loans opinion never cites to Glenn.

[65]. Rapp, supra note 5 (“[C]ourts have universally embraced veil piercing in the LLC context . . . .”).

[66]. 666 S.E.2d 107 (N.C. 2008).

[76]. Id. at 114. Note that the court uses the phrase “corporate” even though it is referring specifically to Ridgeway Brands Manufacturing, LLC.

[78]. The court clarified:

In early 2003 Heflin, Edwards, and White announced the merger of Ridgeway and Brands. Although the formalities were never concluded, the merger became a de facto reality. In early 2003, Brands became the sole purchaser of cigarettes manufactured by Ridgeway. Ridgeway allegedly became “a corporation without a separate mind, will or existence of its own[,] . . . operated as a mere shell to perform for the benefit of . . . [Brands], Edwards, White and Heflin.”

Id. at 109–10 (alterations in original). Later, the court states, “[t]o support its effort to pierce the corporate veil, plaintiff alleged in the amended complaint that Heflin, Edwards, and White exhibited control over Ridgeway . . . .” Id. at 110. This is doubly confusing. The court makes absolutely clear that “Ridgeway” refers to the LLC, yet also states that only Heflin was a member of the LLC. Edwards and White were the shareholders in the corporation.

[79]. Again, it is not clear what type of entity resulted from the merger.

[80]. As previously mentioned, the court did not list failure to adhere to formalities as one of the factors. However, it is a Glenn factor that was not explicitly disclaimed.

[81]. No. 1:06CV2, 2006 WL 1431667 (W.D.N.C. 2006).

[84]. No. 5:05CV210, 2006 WL 1642126 (W.D.N.C. 2006).

[90]. The issue was before the court on a motion to dismiss. The court specifically noted that the complaint alleged enough facts to withstand the defendant’s Rule 12(b)(6) motion. Id. at *13.

[93]. As previously mentioned, there is significant debate about whether inadequate capitalization is a valid piercing factor in the LLC context. See supra notes 30–32.

[94]. 704 S.E.2d 307 (N.C. Ct. App. 2011).

[96]. Id. The proposition that a member may be held individually liable for his own tortious conduct is supported by the language of section 57C-3-30 itself. What is problematic is that the court in this case failed to distinguish LLCs from corporations.

[97]. No. 06 CVS 3367, 2009 WL 4644629 (N.C. Super. Ct. Sept. 4, 2009).

[99]. 18 Am. Jur. 2d Corporations § 47 (2012).

[100]. L’Heureux Enter., 2009 WL 4644629, at *8.

[102]. No. 09-01055-8-JRL, 2011 WL 874140 (Bankr. E.D.N.C. Mar. 11, 2011).

[105]. 625 S.E.2d 800 (N.C. Ct. App. 2006).

[106]. In re AmerLink, 2011 WL 874140, at *3.

[109]. Glenn v. Wagner, 329 S.E.2d 326, 330–31 (N.C. 1985).

[111]. See, e.g., Gunnings v. Internet Cash Enter. of Asheville, No. 5:06CV98, 2007 WL 1931291, at *6 (W.D.N.C. July 2, 2007); State ex rel. Cooper v. Ridgeway Brands Mfg., LLC, 666 S.E.2d 107, 116 (N.C. 2008).

[112]. Spaulding v. Honeywell Int’l, Inc., 646 S.E.2d 645, 649–50 (N.C. Ct. App. 2007).

[113]. Bear Hollow, L.L.C. v. Moberk, L.L.C., No. 5:05CV210, 2006 WL 1642126, at *17 (W.D.N.C. 2006). Inadequate capitalization was considered inL’Heureux Enter., but the court concluded there was not a sufficient allegation by the plaintiff to merit further inquiry. L’Heureux Enter., Inc. v. Port City Java, Inc., No. 06 CVS 3367, 2009 WL 4644629, at *9 (N.C. Super. Ct. Sept. 4, 2009).

[114]. Bear Hollow, 2006 WL 1642126, at *17. In Anderson, the company had one person who acted as the officer, director, and registered agent. Anderson v. Dobson, No. 1:06CV2, 2006 WL 1431667, at *7 (W.D.N.C. 2006). The court concluded that such a showing, without more, is insufficient to pierce the corporate veil. Id.

[115]. Bear Hollow, 2006 WL 1642126, at *17.

[116]. Ridgeway, 666 S.E.2d at 114.

[117]. See, e.g., Commonwealth Mut. Fire Ins. v. Edwards, 32 S.E. 404, 406 (N.C. 1899) (“One of [the] great dangers is the risk of insolvency arising from the want of any personal liability of their stockholders, and the uncertain, and perhaps fictitious, nature of their assets. Some are afflicted with what may be called ‘congenital’ insolvency. They are born insolvent, capitalized into insolvency at the moment of their creation, and eke out a precarious existence in an apparent effort to solve the old paradox of living on the interest of their debts. Such corporations are not only intrinsically dangerous, but lay the foundation for an unjust suspicion of all other corporate bodies.”); Stephen B. Presser, Thwarting the Killing of the Corporation: Limited Liability, Democracy, and Economics, 87 Nw. U. L. Rev. 148, 165 (1992) (“If the shareholder or shareholders deliberately incorporate with initial capital they know to be inadequate to meet the expected liabilities of the business they intend to be doing, they are engaging in an abuse of the corporate form, and ought to be individually liable when those liabilities actually occur.”).

[118]. Robinson, supra note 5, § 2.10(b).

[119]. North Carolina Limited Liability Company Act, N.C. Gen. Stat. § 57C-4-06 (2011).

[120]. The statute notes:

No distribution may be made if, after giving effect to the distribution:

(1) The limited liability company would not be able to pay its debts as they become due in the usual course of business; or

(2) The limited liability company’s total assets would be less than the sum of its total liabilities plus, unless the operating agreement provides otherwise, the amount that would be need, if the limited liability company were to be dissolved at the time of distribution, to satisfy the preferential rights upon dissolution of members whose preferential rights are superior to the rights of the member receiving the distribution.

Id. § 57C-4-06(a). A notable criticism of using undercapitalization as a piercing factor for LLCs is that it is difficult to determine what level of capitalization is adequate. Vandervoort, supra note 19, at 73. Section 57C-4-06(a) effectively provides the solution.

[121]. N.C. Gen. Stat. § 57C-4-07.

[122]. See supra notes 31–33 and accompanying text.

[123]. See, e.g., State ex rel. Cooper v. NCCS Loans, Inc., 624 S.E.2d 371 (N.C. Ct. App. 2005) (explaining that the defendant was charging interest in excess of 400% while engaging in conduct in disregard of consumer protection laws).

[124]. Robinson, supra note 5, § 2.10(b).

[125]. Vandervoort, supra note 19, at 62.

[126]. See generally Robert B. Thompson, The Limits of Liability in the New Limited Liability Entities, 32 Wake Forest L. Rev. 1 (1997).

[129]. North Carolina Limited Liability Company Act, N.C. Gen. Stat. § 57C-2-20(a) (2011).

[132]. See Presser, supra note 27 (“Most limited liability company statutes allow members to manage the LLC. This provision illustrates a legislative intent to allow small, one-person and family-owned businesses the freedom to operate their companies themselves and still enjoy freedom from personal liability.”).

[133]. Robinson, supra note 5, § 2.10(b).

[135]. See Vandervoort, supra note 19, at 60.

[136]. Robinson, supra note 5, § 2.10(b).

[137]. North Carolina Limited Liability Company Act, N.C. Gen. Stat. § 57C-2-21(a) (2011).

[140]. Vandervoort, supra note 19, at 67.

[141]. For example, there are usually requirements to hold annual meetings, elect directors and officers, maintain records, and issue stock certificates. Eric Fox,Piercing the Veil of Limited Liability Companies, 62 Geo. Wash. L. Rev. 1143, 1162 (1994).

[142]. John H. Matheson & Raymond B. Eby, The Doctrine of Piercing the Corporate Veil in an Era of Multiple Limited Liability Entities: An Opportunity to Codify the Test for Waiving Owners’ Limited-Liability Protection, 75 Wash. L. Rev. 147, 175 (2000).

[143]. Vandervoort, supra note 19, at 68.

[144]. Easterbrook & Fischel, supra note 6, at 89.

[145]. Glenn v. Wagner, 329 S.E.2d 326, 330 (N.C. 1985).

[146]. See supra notes 19–20.

[147]. See supra notes 25, 34–35 and accompanying text.

[148]. See supra notes 23, 30 and accompanying text.