13 Wake Forest L. Rev. Online 42

Brandon J. Johnson[1]

Introduction

The North Carolina Supreme Court’s recent decision to reverse course on partisan gerrymandering has garnered national attention.[2] In the court’s third opinion issued in Harper v. Hall,[3] (“Harper III”) a newly elected 5-2 conservative majority of the state supreme court overruled the first opinion[4] authored by the previous 4-3 liberal majority and declared partisan gerrymandering to be a nonjusticiable political question.[5] Election law and constitutional law scholars have produced reams of content questioning how the ruling would impact the U.S. Supreme Court’s pending consideration of the state court’s prior decision in the case.[6] Many questioned whether the state court’s decision would cause the Court to dismiss the initial appeal.[7]

As it turned out, the U.S. Supreme Court’s ruling in what would be known as Moore v. Harper[8] was a significant election law case that expanded the federal judiciary’s role in regulating federal and even state elections. The Supreme Court’s opinion in the case received significant national attention and was largely greeted with a sigh of relief by many scholars and commentators who worried that the Court would adopt an extreme version of a fringe theory known as the Independent State Legislature Theory.[9] Indeed, the importance of the U.S. Supreme Court’s decision regarding the Independent State Legislature Theory has been the primary focus of the commentary surrounding Harper v. Hall and Moore v. Harper, and rightly so.[10] If the Court had adopted the most extreme version of the theory, state legislatures—including (and perhaps especially) significantly gerrymandered legislatures—would have free rein to craft election regulations that entrenched partisan advantages with no constitutional guardrails. Though the Court rejected this approach, the Moore majority left the door open for the U.S. Supreme Court to act as the final arbiter of state election practices, which by itself has caused significant consternation among election law scholars.[11]

Given the national consequences of Moore v. Harper, however, the state court decision Harper III has been largely ignored. While this oversight is understandable, an examination of the North Carolina Supreme Court’s opinion in the case yields vital insight into the ways in which state courts can hide behind a veneer of judicial independence while actually using state politics and polarization to reshape state law. This insight may yield immediate practical consequences given that partisan gerrymandering litigation is currently ongoing in approximately one-third of the states.[12]

The dissent in Harper III provides a searing indictment of the majority’s reasoning and sets forth a cogent argument explaining why the opinion is an incorrect interpretation of the North Carolina constitution. The analysis that follows in this Essay will not rehearse the persuasive criticisms leveled by the dissent. Rather, it will focus on two ways in which the majority opinion may provide insight into how state courts can use the traditional tools of judicial review to reshape a state’s political culture. After providing a brief sketch of the procedural history of Harper I, II, and III in Part I, Part II of this Essay then explores the ways in which the opinion attempts to enshrine an exceptionally narrow vision of originalism as the only acceptable method of interpreting North Carolina’s constitution. Part III criticizes the way in which the Harper III majority further entrenches an incorrect understanding of political accountability.

While the examination below is limited to the rhetoric and reasoning employed by the North Carolina Supreme Court, it should serve as a case study for how easy it can be for state courts to affect a state’s political and policy landscape without attracting much notice.

I. The Procedural Path

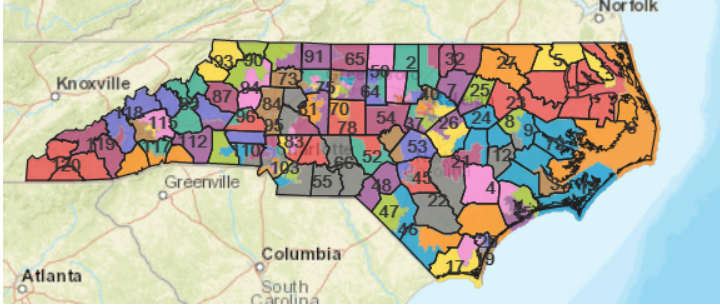

A quick (and by no means exhaustive) recap of the procedural history of the Harper opinions will illuminate the unusual issues created by the state court’s recent ruling and facilitate the discussion that follows. The litigation began after the North Carolina General Assembly issued a new districting map after the 2020 census.[13] Multiple parties filed suit alleging inter alia that the map employed unconstitutional partisan gerrymanders in violation of the North Carolina Constitution’s guarantee of free elections and the state’s equal protection clause.[14] In January 2022, a three-judge panel of the Wake County Superior Court ruled that partisan gerrymandering claims “presen[t] nonjusticiable, political questions” under the state constitution.[15]

Less than a month later, the state supreme court heard the case directly and reversed the lower court’s ruling.[16] The 4-3 majority in what would become known as Harper I held that partisan gerrymandering claims are justiciable and the “extreme” gerrymanders in the challenged districting map violated the state constitution’s free elections clause, equal protection clause, free speech clause, and freedom of assembly clause.[17]

While the state legislature proceeded to draft new districting maps to comply with Harper I, the litigation continued, and the U.S. Supreme Court agreed to hear a challenge to this ruling under the name Moore v. Harper.[18] The Supreme Court case garnered national attention, in part, because the petitioners advanced arguments under the Independent State Legislature Theory. The Independent State Legislature Theory posits that only the state legislature has any say in federal elections[19] because the Elections Clause of the U.S. Constitution instructs that “The Times, Places and Manner of holding Elections for Senators and Representatives shall be prescribed in each State by the Legislature thereof.”[20] Put another way, the state constitution itself places no limits on the legislature’s ability to regulate federal elections leaving state courts with no authority to interpret state constitutional provisions in order to second guess election related legislation.

But while the U.S. Supreme Court litigation proceeded, various parties challenged the second districting map that the legislature drafted in response to Harper I and the case made its way back to the state supreme court.[21] In a December 2022 opinion, now known as Harper II[22], the same 4-3 majority that issued the Harper I opinion ruled that the map for the state house was constitutionally adequate but the maps for the state senate and the federal congressional districts still contained unconstitutional partisan gerrymanders.[23]

In between oral arguments in Harper II and the issuance of the opinion, the North Carlina midterm elections occurred.[24] North Carolina’s supreme court justices are elected in partisan contests, and two of the Democratic justices who had signed on to the Harper II majority were replaced by conservative challengers.[25] As a result of this change in personnel, the new 5-2 conservative majority expressed concern that the Harper II majority had “overlooked or misapprehended” a point “of fact or law,”[26] and granted a petition for rehearing.[27]

On April 28, 2023 this newly minted majority “withdrew” Harper II and “overruled” Harper I, finding that partisan gerrymandering claims presented a nonjusticiable political question.[28] The U.S. Supreme Court then issued its opinion in Moore v. Harper on June 27, 2023.[29] The majority opinion determined that the Court still had standing to decide the initial case but affirmed the Harper I decision.[30] In doing so, the Court rejected the state defendants’ primary legal argument regarding the Elections Clause and reaffirmed that “[t]he Elections Clause does not insulate state legislatures from the ordinary exercise of state judicial review.”[31] The Court did, however, reserve for itself the right to pass judgment on whether state courts correctly interpreted questions of state election law under state constitutions,[32] a significant increase in the Court’s review of state election laws.[33]

With this procedural sketch in place, this Essay now returns to its primary focus: an examination of the warning signs advocates, policymakers, and public law scholars should glean from the North Carolina Supreme Court’s opinion in Harper III. As discussed in the introduction, the focus of this examination will not be on the merits of the majority opinion as the dissent has already done an admirable job dissecting that on its own terms.[34] Instead, the remainder of this Essay delves into the more far-reaching consequences of the opinion. Though the ramifications of the majority’s opinion are limited to North Carolina, they provide a cautionary tale for the ways in which state courts—particularly those with elected judges—can involve the judiciary in the political fortunes of the state.

II. Regressive Originalism

Perhaps the most sweeping consequence of the opinion may be the majority’s efforts to enshrine originalism (and a crabbed version of originalism, at that) as the only acceptable methodology of constitutional interpretation.[35] From the first few pages, Harper III makes this view of constitutional interpretation clear. For example, on the second page of the opinion, the majority writes: “As the courts apply the constitutional text, judicial interpretations of that text should consistently reflect what the people agreed the text meant when they adopted it.”[36] This appeal to the original public meaning[37] of the state’s constitution returns time and again throughout the opinion, including the following concluding admonition: “Recently, this Court has strayed from this historic method of interpretation to one where the majority of justices insert their own opinions and effectively rewrite the constitution.”[38] This language makes clear that the current majority of the North Carolina Supreme Court views originalism as the only legitimate method of constitutional interpretation.

The current state court majority is not alone in its application of originalist methodology, nor unique in its attempts to privilege this school of constitutional interpretation above all others.[39] Nor is an originalist approach to interpreting the North Carolina constitution without precedent.[40] The version of originalist methodology operationalized in the Harper III opinion, however, is surprisingly (almost shockingly) pernicious.

As an initial matter, the majority seems to advocate for both original public meaning originalism and original intent originalism, despite the latter theory having been all but (though not entirely)[41] abandoned by originalism’s defenders.[42] In its introduction, for example, the majority insists that “judicial interpretations of [constitutional] text should consistently reflect what the people agreed the text meant when they adopted it”—a classic formulation of original public meaning originalism.[43] But when returning to a discussion of constitutional interpretation, the majority seems to urge an “original intent” approach, asserting that “courts determine the meaning of a constitutional provision by discerning the intent of its drafters when they adopted it.”[44]

The reliance on this largely abandoned[45] version of originalism is only one example of how the Harper III majority is attempting to mandate not just originalism, but a regressive vision of originalism. By focusing on the actual intent of the drafters of the document, a court limits the potential interpretations of a constitution to the world view of individuals at a fixed point in time—a world view that is in many ways incompatible with the present day. Additionally, by employing both original intent originalism and original public meaning originalism, the Harper III majority can switch back and forth between whichever methodology best supports its desired result, eliminating originalism’s supposed virtue of constraining judicial discretion.[46]

Nor does the majority escape the “law office historian” pitfalls that plague many originalist opinions.[47] For example, the court devotes several pages to recounting the history of the Glorious Revolution in a befuddling attempt to show that the state constitutional clauses cited by the plaintiffs in the underlying cases were directed at protecting North Carolinians from voting regulations designed to benefit the king.[48] As an initial matter, this history says nothing about the clauses’ relationship to gerrymandering—again, a phenomenon that was not even in the lexicon for more than a century.[49] But even taking the majority’s argument on its own terms, the historical narrative provided arguably supports applying the free elections clause to partisan gerrymandering rather than undermining such an interpretation.[50] The majority declares, for example, that one reason for the prohibition on dividing counties to make new districts comes in part from King James II’s practices of “adjusting a county’s or borough’s charter to embed the king’s agents and ensure a favorable outcome for the king in the 1685 election.”[51] The majority reiterates that “[i]n some instances these adjustments altered who could vote in order to limit the franchise to those most likely to support the king’s preferred candidates.”[52] But this type of result-oriented intervention is exactly the reason parties challenge partisan gerrymanders.

But beyond succumbing to these more common problems with originalist methodology, the majority also employs a particularly rigid approach to originalism that would severely inhibit applications of the state constitution to modern developments. The most plausible reading of the majority’s analysis of whether the constitution applies to partisan gerrymandering, for example, is that the state constitution is essentially irrelevant to any subject not explicitly discussed.[53] Because the constitution does not mention gerrymandering, the majority says, that document is irrelevant to evaluating any gerrymandering challenges.[54] But even staunch originalists like Ilan Wurman accept that applying the original meaning of the text does not mean that a constitution must anticipate and discuss every eventuality in order to apply to the subject at hand.[55] The fact that the U.S. Constitution makes no mention of the internet, for example, does not prevent originalists from agreeing that the protections of the First Amendment apply to this 21st century medium.[56]

In support of this tightly cabined interpretation of the state constitution, the majority highlights a case from the 1780s striking down a statute that directly conflicted with the then governing constitution by eliminating the right to a jury trial in cases where the state confiscated loyalist property.[57] The constitution at the time promised a jury trial “in all Controversies at Law respecting property.”[58] But simply because the first statute, which was deemed unconstitutional in the state, directly conflicted with express language in the constitution does not impose a lasting and immovable requirement that judicial review of a legislative act is permissible only if the constitution speaks directly to the subject at hand.[59]

The majority even attempts to graft on some version of this explicit language requirement to its discussion of the U.S. Constitution, asserting that the lack of any specific mention of partisan gerrymandering in that document demonstrates the framers’ intent to exclude the federal courts from any such oversight. The majority further claims that “[t]he framers could have limited partisan gerrymandering in the [U.S.] Constitution or assigned federal courts a role in policing it, but they did not.”[60] To take this statement at face value shows the absurdity that this explicit acknowledgement requirement would impose.[61] The term “gerrymander” did not even exist until more than two decades after the U.S. Constitution was ratified.[62] Nor did the U.S. Constitution make any mention of “partisanship” (or “factionalism” as this concept was more commonly called at the time) because one of the goals of the famers was to avoid factional divisions.[63]

The end result of this interpretative approach is that the majority seems far too comfortable with an interpretation of the North Carolina constitution that reflects a polity of exclusion. The opinion at one point even asserts that because the original understanding of the state constitution’s “free elections” clause still limited the franchise to land-holding “freemen,” the clause cannot be construed to prohibit limitations on voting rights beyond coercion and intimidation.[64] An application of such a regressive version of originalism is especially misplaced in deciding questions relating to elections based on a constitutional text ratified when the franchise was extremely limited. The majority, for example, argues that because the original North Carolina Constitution adopted in 1776 contained free elections and freedom of assembly clauses while still allowing the legislature to draw malapportioned districting maps, these same clauses should not be used to restrict legislative map drawing today.[65] But this rationale would also allow election regulations that discriminated on the basis of race, gender, sexual orientation, and even status as a property owner, as long as subsequent amendments did not address the specific types of discriminatory regulations employed. Indeed, the Harper III majority simply ignores fundamental developments in both federal and state constitutional law that took place after the ratification of the state’s first constitution—ignoring the fact that North Carolina adopted a new constitution in 1868 and again in 1971 and has significantly amended the document in the last two centuries.[66]

Even when the majority makes general assertions of law, it relies on authority that further illustrates the regressive results of the justices’ chosen interpretive methodology. The majority, for example, cites to a 1944 case, State v. Emery,[67] to support its assertion that “[constitutions] should receive a consistent and uniform construction . . . even though circumstances may have so changed as to render a different construction desirable.”[68] But the “consistent and uniform construction” urged by the court in Emery enshrined the barring of women from serving as jurors in the state based on language in the then governing constitution stating that “[n]o person shall be convicted of any crime but by the unanimous verdict of a jury of good and lawful men in open court.”[69] To be clear, the majority does not endorse (or even mention) the holding of Emery, but it is telling that the vision of originalism espoused by the Harper III opinion is the exact same reading of the state constitution that prohibited women from serving on juries as late as 1944.[70] The fact that this case would be used to support the majority’s preferred methodology when other options are readily available seems questionable.

In a similarly telling choice, the majority issues another generic statement regarding the nature of the state constitution, asserting that the document “‘is in no matter a grant of power.’”[71] This benign quote comes from McIntyre v. Clarkson,[72] but the opinion then traces the origins of this quote to Lassiter v. Northampton County Board of Elections,[73] a 1958 case that upheld North Carolina’s reading requirement at the polls, despite clear evidence that the requirement was used to impede the ability of black North Carolinians to vote.[74] Again, the choice to trace this general point of law to a case upholding racially discriminatory voting laws indicates that the majority is either unaware of, or indifferent to, the regressive results of its methodological approach.[75]

In fact, the majority opinion makes clear that the North Carolina constitution would not ban racial gerrymanders, or any other type of racially motivated voting restrictions, leaving such practices banned only by the U.S. Constitution.[76] The court’s emphasis on requiring an explicit, specific textual restriction in the Constitution leads to a listing of what the majority appears to consider the only permissible avenues for judicial review of legislative districting acts.[77] Notably absent from this list is any prohibition on district maps that discriminate based on race.[78] The opinion also quotes heavily from a prior state supreme court decision, Dickson v. Rucho,[79] to emphasize the difficulty in identifying a judicially manageable standard for evaluating partisan gerrymanders.[80] What goes unmentioned in this discussion, however, is that the U.S. Supreme Court vacated Dickson I because the districting map employed racial gerrymanders as well.[81]

Taken together, the majority’s vision for constitutional interpretation inescapably leads to a regressive application of the state’s constitution. Because the rhetoric here sounds in a traditional application of judicial review, however, the Harper III majority has laid out a blueprint for similarly inclined state court majorities to manipulate theories of constitutional interpretation to essentially control state electoral politics while shielding themselves from political accountability. With this concern in mind, the Essay now turns to an examination of the majority’s misleading invocation of political accountability as justification for its holding.

III. Manipulation of Political Accountability

The other rhetorical move made by the Harper III majority that is likely to have long reaching impact is the weaponization of political accountability. The majority relies on the time honored trope that the state legislature is the true “people’s branch” in state government, asserting from the beginning of the opinion that “[t]he people exercise [the political] power [granted to them by the state constitution] through the legislative branch, which is closest to the people and most accountable through the most frequent elections.”[82] The majority then implicitly ties this version of “accountability” to the state legislature’s ability to implement “the will of the people.”[83]

This lionization of state legislatures as the branch “closest to the people” has been effectively rebutted by legal scholars like Miriam Seifter.[84] As Seifter demonstrates, officials elected in statewide elections are often more representative of the whole people of a state than are state legislators.[85] In North Carolina, the very same justices who disclaim sufficient accountability are all elected statewide.[86] Indeed, it is because of the elected (and partisan) nature of these judicial offices that Harper II was granted a rehearing.[87] So, even from a threshold perspective, the democratic legitimacy foundation for the Harper III opinion is on shaky ground.

But this unsupported trope of American democracy has even less to recommend it in the context of a gerrymandering challenge. The essence of a claim of gerrymandering is that the body elected by the gerrymandered map is unrepresentative of the people.[88] Even a majority of voters cannot effectively hold a gerrymandered legislature “accountable” if the gerrymander is extreme enough to consistently transform minority preference into majority representation.[89] But the Harper III majority ignores this reality, blithely asserting that “those whose power or influence is stripped away by shifting political winds cannot seek a remedy from courts of law, but they must find relief from courts of public opinion in future elections.”[90] Indeed, the majority’s assurances then that “opponents of a redistricting plan are free to vote their opposition,”[91] ring hollow when addressing claims that the redistricting process has effectively undermined the ability of even a majority of voters to hold their legislature “accountable” in the traditional sense.

The Harper III majority also recounts language from Rucho v. Common Cause[92] that reiterates a “long-standing … myth[] about the rational, policy-oriented voter.”[93] The majority faults the Harper I opinion for focusing too much on the role of partisan affiliation in elections.[94] The opinion confidently asserts, for example, that “voters elect individual candidates in individual districts, and their selections depend on the issues that matter to them, the quality of the candidates, the tone of the candidates’ campaigns, the performance of an incumbent, national events or local issues that drive voter turnout, and other considerations.”[95] But, as I have written previously, much of modern political science literature documenting voter behavior indicates that voters are not nearly this nuanced, and instead partisan affiliation is a far better predictor of voter behavior than any of the factors identified in Rucho and parroted in Harper III.[96]

The majority quotes freely from Rucho and incorporates much of that decision’s language cautioning against involving the “unaccountable” federal judiciary against involving itself in the inherently political redistricting process.[97] Regardless of one’s views on the correctness of Rucho, it is clear that the accountability concerns discussed in the case stem from the federal judiciary’s position as an unelected branch of government.[98] Indeed, the connection between political accountability and the unelected nature of the federal judiciary is quoted in full by the Harper III majority: “Consideration of the impact of today’s ruling on democratic principles cannot ignore the effect of the unelected and politically unaccountable branch of the Federal Government assuming such an extraordinary and unprecedented role.”[99]

But recall that almost the entire North Carolina judiciary, including the justices of the state supreme court, are elected.[100] The Justices in particular, are elected statewide and are not subject to the gerrymandered districting maps.[101] As noted above, this makes them, arguably, more accountable to the people of North Carolina because the statewide election better reflects the full electorate than does a manipulated state legislature district.[102] Nor are these elected judges above the political fray because they are chosen in partisan elections appearing on the ballot with their party affiliation clearly identified.[103] The Harper III majority cautions against involving the judiciary in “[c]hoosing political winners and losers” because doing so “creates a perception that the courts are another political branch.”[104] But in North Carolina, the judiciary is, arguably, a political branch. The state’s justices owe their offices to a political election that is influenced, in part at least, by the partisan, political preferences of the voters.[105] This is not to say that there is no difference between a justice and a legislator. Rather, this criticism demonstrates why the Harper III majority’s reliance on the accountability justifications in Rucho are so misplaced.

The majority leans into this accountability narrative, despite eventually acknowledging the elected nature of the state’s judiciary.[106] Indeed, though still pushing its assertion that the state legislature is the “most accountable” branch of the state government, the majority does recognize that with the implementation of an elected judiciary “judges in North Carolina become directly accountable to the people through elections.”[107] And the Harper III majority itself seems to acknowledge that the judicial elections play (or should play) a role in shaping North Carolina law.[108] One of the criticisms levelled against the Harper II opinion is that the “four-justice majority issued its Harper II opinion on 16 December 2022 [after the most recent judicial election] when it knew that two members of its majority would complete their terms on this Court just fifteen days later.”[109] It is hard to read this statement as anything other than a concession that a change in the partisan makeup on the court would (and should) change the outcome of cases.

Yet the majority consistently focuses on the supposed dangers posed to the separation of powers by involving the judiciary in “policymaking.”[110] The majority insists, for example, that the lack of an explicit reference to gerrymandering means that any court exercising judicial review of a gerrymandered map is engaged in policymaking.[111] Such judicial policymaking, we are told, “usurps the role of the legislature by deferring to [the court’s] own preferences instead of the discretion of the people’s chosen representative.”[112]

But, in addition to the unsound political accountability foundation for this view of the role of an elected judiciary, the majority’s vision of “policymaking” ignores the reality that the decision to close the courthouse doors to partisan gerrymandering claims is also a policy choice.

In refusing to apply the state constitution’s equal protection clause to partisan gerrymandering claims, for example, the majority asserts that “the fundamental right to vote on equal terms simply means that each voter must have the same weight.”[113] The court dismisses any independent application of the clause to elections by claiming that any equal protection concerns raised by election procedures are fully addressed by the requirements in Article II that each state legislator “represent, as nearly as may be, an equal number of inhabitants.”[114] But, by insisting that the state constitution’s equal protection clause only addresses the “weight” of each individual vote, and by taking a step further and confining “weight” to only the number of voters represented by each representative, the majority is engaging in exactly the same type of policymaking it claims made the Harper I and Harper II decisions illegitimate.

The inconsistent, almost incoherent ways in which the Harper III majority has employed discredited myths about political accountability and the role of an elected judiciary will impact election law and constitutional interpretation in North Carolina far beyond the holding of the case. With more than three quarters of states employing at least some form of elections as part of their judicial selection process,[115] a failure to confront the realities of an elected judiciary will continue to leave open opportunities for state courts to employ fantasies of political accountability to reshape their state’s political processes. While acknowledging the political nature of an elected judiciary may not stop state courts from reaching their desired results, it will at least require state judiciaries to honestly assess their own political role in deciding separation of powers disputes.

Conclusion

While the U.S. Supreme Court’s opinion in Moore v. Harper captured national attention, the Harper III majority also rejected the broadest version of the Independent State Legislature Theory advanced in the Moore briefing. In doing so, the majority recognizes that the courts—and by implication the state constitution—do have some role to play in the districting process: “Under the North Carolina Constitution, redistricting is explicitly and exclusively committed to the General Assembly by the text of the constitution. The Executive branch has no role in the redistricting process, and the role of the judicial branch is limited by the principles of judicial review.”[116] But, as with the opinion in Moore, the majority opinion in Harper III will have a longer reach beyond a specific holding on partisan gerrymandering.

This Essay has specifically focused on the adoption of a regressive form of originalism, which ultimately results in a polity of exclusion and inhibits the court’s potential to employ the state constitution in addressing contemporary challenges. The Harper III majority’s reliance on a rigid and outdated version of originalism is deeply troubling. By adhering to a carefully crafted quasihistorical context that fails to account for societal evolution and progress, the state court disregards the dynamic nature of constitutional principles. And the majority’s willingness to interpret the state constitution in an intentionally exclusionary way will continue to echo through the court’s jurisprudence.

The Essay has also demonstrated the danger of relying on “mythical” notions of political accountability. The majority’s use of these largely unrealistic tropes to decry judicial policymaking, while conveniently overlooking the fact that the North Carolina judiciary is elected and therefore accountable to the public, highlights the ways in which state courts can weaponize accountability not just in North Carolina, but nationwide. As of July of this year, litigation around partisan gerrymandering is ongoing in at least seventeen states.[117] Because the Supreme Court has closed the door on such claims under federal law, state courts remain the only viable venue to address partisan gerrymanders.[118] Left unchecked, the Harper III opinion provides a dangerous blueprint—regressive originalism and unsubstantiated notions of political accountability—that state courts may apply to these claims in ways that will significantly influence state election processes (and likely results) for the foreseeable future.

Election law, constitutional law, and federalism scholars should take note of the jurisprudential tactics employed in the Harper III majority as they continue to work to protect American democracy.

-

*. Assistant Professor of Law at University of Nebraska College of Law. Many thanks to Anna Arons, Eric Berger, Kristen Blankley, Tyler Rose Clemons, Haiyun Damon-Feng, Dorien Ediger-Soto, Danielle C. Jefferis, Kyle Langvardt, Elise Maizel, Matthew Schaefer, and the members of the University of Nebraska College of Law Faculty Workshop for their thoughts and comments. ↑

-

. See, e.g., Derek Muller, What happens to Moore v. Harper after the latest North Carolina Supreme Court decision in the partisan gerrymandering case?, Election Law Blog (Apr. 28, 2023, 10:04 AM), https://electionlawblog.org/?p=135865. ↑

-

. Harper v. Hall, 886 S.E.2d 393 (N.C. 2023) (hereinafter “Harper III”). ↑

-

. Harper v. Hall, 868 S.E.2d 499 (N.C. 2022) (hereinafter “Harper I”) (overruled by Harper III, 886 S.E.2d 393). ↑

-

. Harper III, 886 S.E.2d 393. ↑

-

. See, e.g., Muller, supra note 1. ↑

-

. See, e.g., Hansi Lo Wang, A North Carolina court overrules itself in a case tied to a disputed election theory, NPR (Apr. 28, 2023, 12:25 PM), https://www.npr.org/2023/04/28/1164942998/moore-v-harper-north-carolina-supreme-court. ↑

-

. 143 S. Ct. 2065 (2023). ↑

-

. See, e.g., Rick Hasen, Separating Spin from Reality in the Supreme Court’s Moore v. Harper Case: What Does It Really Mean for American Democracy and What Does It Say About the Supreme Court?, Election Law Blog (June 27, 2023, 3:29 PM), https://electionlawblog.org/?p=137129. ↑

-

. See e.g., id. ↑

-

. See e.g., id. ↑

-

. Redistricting Litigation Roundup, Brennan Center for Justice (updated July 7, 2023), https://www.brennancenter.org/our-work/research-reports/redistricting-litigation-roundup-0. ↑

-

. Harper III, 886 S.E.2d at 401. ↑

-

. Id. ↑

-

. Id. at 402. ↑

-

. Id. at 403. ↑

-

. Harper I, 868 S.E.2d at 559. ↑

-

. 142 S. Ct. 2901 (2022) (mem.). ↑

-

. See Brandon J. Johnson, The Accountability-Accessibility Disconnect, 58 Wake Forest L. Rev. 65, 90 (2023). ↑

-

. U.S. Const. art. I, § 4, cl. 1. ↑

-

. Harper III, 886 S.E.2d at 408. ↑

-

. 881 S.E.2d 156 (2022) (hereinafter “Harper II”). ↑

-

. Id. at 181. ↑

-

. See Ethan E. Horton & Eliza Benbow, Two Republicans Win Seats On The NC Supreme Court, Flipping Majority, The Daily Tar Heel (Nov. 9, 2022), https://www.dailytarheel.com/article/2022/11/city-nc-supreme-court-2022-election-results. ↑

-

. Id. ↑

-

. Harper III, 886 S.E.2d at 399–400 (quoting N.C. R. App. P. 31(a)). ↑

-

. Id. at 409. ↑

-

. Id. at 401. ↑

-

. 143 S.Ct. 2065 (2023). ↑

-

. Id. at 2079, 2081. ↑

-

. Id. at 2081. ↑

-

. Id. at 2088. ↑

-

. See Hasen, supra, note 8. ↑

-

. Harper III, 886 S.E.2d at 449–78 (Earls, J., dissenting). ↑

-

. Keith E. Whittington, Originalism: A Critical Introduction, 82 Fordham L. Rev. 375, 377 (2013) (“At its most basic, originalism argues that the discoverable public meaning of the Constitution at the time of its initial adoption should be regarded as authoritative for purposes of later constitutional interpretation.”). ↑

-

. Harper III, 886 S.E.2d at 399. ↑

-

. Whittington, supra note 34, at 380 (“Originalist theory has now largely coalesced around original public meaning as the proper object of interpretive inquiry.”). ↑

-

. Harper III, 886 S.E.2d at 448. ↑

-

. See, e.g., New York State Rifle & Pistol Ass’n, Inc. v. Bruen, 142 S. Ct. 2111, 2130 (2022) (“[R]eliance on history to inform the meaning of constitutional text—especially text meant to codify a pre-existing right—is, in our view, more legitimate, and more administrable, than asking judges to ‘make difficult empirical judgments’ about ‘the costs and benefits of firearms restrictions,’ especially given their ‘lack [of] expertise’ in the field.” (quoting McDonald v. Chicago, 561 U.S. 742, 790–91 (2010))). ↑

-

. See Harper III, 886 S.E.2d at 412–14 (collecting cases). ↑

-

. See, e.g., Scott A. Boykin, Original-Intent Originalism: A Reformulation and Defense, 60 Washburn L.J. 245 (2021). ↑

-

. Id. at 246. ↑

-

. Harper III, 886 S.E.2d at 399. ↑

-

. Id. at 431. ↑

-

. See Whittington, supra note 34, at 382. ↑

-

. See, e.g., Lawrence B. Solum, The Constraint Principle: Original Meaning and Constitutional Practice (2019) (asserting that “constraint” is a virtue agreed upon by most strands of originalist scholarship); but see William Baude, Originalism as a Constraint on Judges, 84 U. Chi. L. Rev. 2213, 2214 (2018) (claiming that “originalist scholars today are much more equivocal about the importance and nature of constraining judges”). ↑

-

. See, e.g., Saul Cornell, Heller, New Originalism, and Law Office History: Meet the New Boss, Same as the Old Boss, 56 UCLA L. Rev. 1095 (2009). ↑

-

. Harper III, 886 S.E.2d.at 434–38. ↑

-

. See Erick Trickey, Where Did the Term “Gerrymander” Come From?, Smithsonian Mag. (July 20, 2017), https://www.smithsonianmag.com/history/where-did-term-gerrymander-come-180964118/. ↑

-

. Harper III, 886 S.E. 2d at 434–38. ↑

-

. Id. at 435 (emphasis added). ↑

-

. Id. (emphasis added). ↑

-

. See Harper III, 886 S.E.2d at 415 (“When we cannot locate an express, textual limitation on the legislature, the issue at hand may involve a political question that is better suited for resolution by the policymaking branch.”). ↑

-

. See, e.g., Harper III, 886 S.E.2d at 400 (emphasis added) (“Our constitution expressly assigns the redistricting authority to the General Assembly subject to explicit limitations in the text. Those limitations do not address partisan gerrymandering. It is not within the authority of this Court to amend the constitution to create such limitations on a responsibility that is textually assigned to another branch.”). ↑

-

. Ilan Wurman, What is originalism? Debunking the myths, The Conversation (Oct. 24, 2020, 12:03 PM), https://theconversation.com/what-is-originalism-debunking-the-myths-148488. ↑

-

. Neil M. Gorsuch, Justice Neil Gorsuch: Why Originalism Is the Best Approach to the Constitution, Time (Sept. 6, 2019, 8:00 AM), https://time.com/5670400/justice-neil-gorsuch-why-originalism-is-the-best-approach-to-the-constitution/. ↑

-

. Harper III, 886 S.E.2d. at 415 (citing Bayard v. Singleton, 1 N.C. (Mart.) 5 (1787)). ↑

-

. Id. (quoting N.C. Const. of 1776, Declaration of Rights § XIV). ↑

-

. As the majority acknowledges, Bayard was the first exercise of judicial review of a statute in North Carolina, and may have been the first instance of a state court striking down a legislative act as contrary to the jurisdiction’s constitution. Id. ↑

-

. Id. at 410. ↑

-

. Id. at 415 (emphasis added) (“[T]he standard of review asks whether the redistricting plans drawn by the General Assembly, which are presumed constitutional, violate an express provision of the constitution beyond a reasonable doubt.”). ↑

-

. Trickey, supra note 48. ↑

-

. See, e.g., The Federalist No. 10 (James Madison). ↑

-

. See Harper III, 886 S.E.2d at 432–33. ↑

-

. Id. at 416–17. ↑

-

. Dr. Troy L. Kickler, North Carolina Constitution Is an Important Governing Document, N.C. Hist. Project, https://northcarolinahistory.org/encyclopedia/1573/ (last visited Sept. 17, 2023). ↑

-

. 31 S.E.2d 858 (N.C. 1944). ↑

-

. Harper III, 886 S.E.2d at 413 (alterations and omissions in Harper III) (quoting State v. Emery, 31 S.E.2d 858, 861 (N.C. 1944)). Notably, the omitted language from the quote would seem to caution against the majority’s decision to reverse a previous pronouncement of constitutional law. The full quote reads: “[Constitutions] should receive a consistent and uniform construction so as not to be given one meaning at one time and another meaning at another time even though circumstances may have so changed as to render a different construction desirable.” Emery, 31 S.E.2d at 861 (emphasized language was omitted from the quote in Harper III). ↑

-

. N.C. Const. art. I, § 13 (1868) (emphasis added). ↑

-

. Harper III, 886 S.E.2d at 413; Emery, 31 S.E.2d at 866. ↑

-

. Harper III, 886 S.E.2d at 414 (quoting McIntyre v. Clarkson, 119 S.E.2d 888, 891 (1961)). ↑

-

. 119 S.E.2d at 891. ↑

-

. 102 S.E.2d 853, 861 (N.C. 1958). ↑

-

. Paul Woolverton, Democrats in 1900 made the NC Constitution racist: Will voters today undo that?, Fayetteville Observer (Mar. 24, 2023, 5:06 AM), https://www.fayobserver.com/story/news/2023/03/24/ncs-constitution-has-a-racist-rule-will-voters-repeal-literacy-tests/70035467007/. ↑

-

. For further discussion of the morality of case citations—specifically in the context of citing to slave cases—see Alexander Walker III, On Taboos, Morality, and Bluebook Citations, Harv. L. Rev. Blog (June 10, 2023). ↑

-

. Compare Harper III, 886 S.E.2d at 449 (holding that “claims of partisan gerrymandering present nonjusticiable, political questions”), with Miller v. Johnson, 515 U.S. 900, 927–28 (holding that redistricting plans aiming to racially segregate voters are federally unconstitutional). ↑

-

. Harper III, 886 S.E.2d at 418 (quoting N.C. Const. art. II, § 3). The only restrictions on apportionment acknowledged by the majority are: (1) state senators must represent a (roughly) equal number of residents; (2) districts must be contiguous; (3); a prohibition on dividing counties to form a new district; and (4) a requirement that districts “remain unaltered” between censuses. Id. ↑

-

. See id. ↑

-

. 766 S.E.2d 238 (N.C. 2014). ↑

-

. See, e.g., Harper III, 886 S.E.2d at 402 (quoting Dickson, 766 S.E.2d at 260). ↑

-

. See Dickson v. Rucho, 137 S. Ct. 2186 (2017) (mem.). The Harper III opinion notes that the state court decision was vacated, but only using the euphemistic language “vacated on federal grounds.” See Harper III, 886 S.E.2d at 402. ↑

-

. Harper III, 886 S.E.2d at 398. ↑

-

. Id. at 398–99. The opinion returns to this theme of identifying the General Assembly as “the people’s branch” of state government. See, e.g., id. at 413 (“The legislative power is vested in the General Assembly, so called because all the people are present there in the persons of their representatives.” (quoting John V. Orth & Paul Martin Newby, The North Carolina State Constitution 95 (2d ed. 2013))); id. at 414 (citations omitted) (“Most accountable to the people, through the most frequent elections, “[t]he legislative branch of government is without question ‘the policy-making agency of our government[.]’” (quoting N.C. Const. art II)). ↑

-

. Miriam Seifter, Countermajoritarian Legislatures, 121 Colum. L. Rev. 1733, 1755–77 (2021); see also Johnson, supra note 18, at 101–02. ↑

-

. Seifter, supra note 83, at 1762–77. ↑

-

. N.C. Const. art IV, § 16. ↑

-

. See supra Part I. ↑

-

. See Kevin Wender, The “Whip Hand”: Congress’s Elections Clause Power as the Last Hope for Redistricting Reform After Rucho, 88 Fordham L. Rev. 2085, 2090 (2020). ↑

-

. For a discussion of the difficulty voters face in using the political process to change election laws, see Johnson, supra note 18, at 109. ↑

-

. Harper III, 886 S.E.2d 393, 423 (N.C. 2023) (quoting Dickson v. Rucho, Nos. 11-CVS-16896, 11-CVS-16940, 2013 WL 3376658, at *1–2 (N.C. Super. Ct. Wake Cnty. July 8, 2013)). ↑

-

. Id. at 443. ↑

-

. 139 S. Ct. 2484 (2019). ↑

-

. Johnson, supra note 18, at 103. ↑

-

. See Harper III, 886 S.E.2d at 428. ↑

-

. Harper III, 886 S.E.2d at 412 (quoting Rucho v. Common Cause, 139 S. Ct. 2484, 2503–04 (2019)). The majority repeats these assertions, again without providing any empirical support for this view of voter behavior. Id. at 428–29. ↑

-

. Johnson, supra note 18, at 104–05. ↑

-

. See, e.g., Harper III, 886 S.E.2d at 413 (quoting Rucho, 139 S. Ct. at 2507). ↑

-

. See Rucho, 139 S. Ct. at 2507. ↑

-

. Harper III, 886 S.E.2d 393, 413 (N.C. 2023) (quoting Rucho, 139 S. Ct. at 2507); see also id. at 427 (alteration in original) (“A judicially discoverable and manageable standard is necessary for resolving a redistricting issue because such a standard ‘meaningfully constrain[s] the discretion of the courts[] and [] win[s] public acceptance for the court’s intrusion into a process that is the very foundation of democratic decision making.’” (quoting Rucho, 139 S. Ct. at 2500)). ↑

-

. N.C. Const. art IV, §16. ↑

-

. Id. ↑

-

. See Seifter, supra note 83, at 1734–41. ↑

-

. See, e.g., Judicial voter guide: 2022 primary election, North Carolina State Board of Elections, (last visited Sept. 17, 2023), https://www.ncsbe.gov/judicial-voter-guide-2022-primary-election. ↑

-

. Harper III, 886 S.E.2d at 399. ↑

-

. See Nat Stern, Don’t Answer That: Revisiting the Political Question Doctrine in State Court, 21 U. Pa. J. Const. L. 153, 177–78 (2018) (observing that elected state court judges do not enjoy the same presumption of judicial independence that attaches to the federal judiciary). ↑

-

. Harper III, 886 S.E.2d at 418. ↑

-

. Id. (citing N.C. Const. of 1868, art IV, § 26). ↑

-

. Id. at 413–14. ↑

-

. Id. at 407 n.5. ↑

-

. See, e.g., Harper III, 886 S.E.2d at 399, 415, 431. The majority also ignores the differences between the ways in which power is separated at the state level instead of the federal level. For further discussion of these differences, see Robert F. Williams, The Law of American State Constitutions 238 (2009) and Helen Hershkoff, State Courts and the “Passive Virtues”: Rethinking the Judicial Function, 114 Harv. L. Rev. 1833 (2001). ↑

-

. See Harper III, 886 S.E.2d at 428 (“[S]ince the state constitution does not mention partisan gerrymandering, the four justices in Harper I first had to make a policy decision that the state constitution prohibits a certain level of partisan gerrymandering.”). ↑

-

. Id. at 431. ↑

-

. Id. at 440. ↑

-

. Id. at 442 (quoting N.C. Const. art. II, §§ 3(1), 5(1)). ↑

-

. Significant Figures in Judicial Selection, Brennan Ctr. for Just. (Apr. 14, 2023), https://www.brennancenter.org/our-work/research-reports/significant-figures-judicial-selection. ↑

-

. Harper III, 886 S.E.2d at 416. ↑

-

. Redistricting Litigation Roundup, Brennan Ctr. for Just., https://www.brennancenter.org/our-work/research-reports/redistricting-litigation-roundup-0 (July 7, 2023). ↑

-

. See generally Rucho v. Common Cause, 139 S. Ct. 2484 (2019) (holding that challenges to partisan gerrymandering are to be made under state statutes and state constitutions—not the U.S. Constitution); see also Alicia Bannon, North Carolina Supreme Court Unleashes Partisan Gerrymandering, Brennan Ctr. For Just. (May 10, 2023), https://www.brennancenter.org/our-work/analysis-opinion/north-carolina-supreme-court-unleashes-partisan-gerrymandering. ↑