By Taylor Anderson

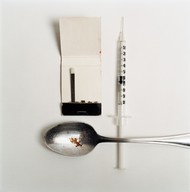

On March 7, 2016, the Fourth Circuit issued its published opinion regarding the criminal case United States v. Alvarado. Jean Paul Alvarado (“Appellant”) appealed his conviction of knowingly and intentionally distributing heroin to Eric Thomas (“Thomas”) with Thomas’ death resulting from the use of the heroin so distributed, in violation of 21 U.S.C. §§ 841(a)(1) and 841(b)(1)(C). On appeal, Appellant contends that the district court erred in three ways during trial. The Fourth Circuit affirmed Appellant’s conviction, holding that the district court did not err in any of the three ways Appellant alleged.

Appellant Convicted of Heroin Distribution

On March 30, 2011, in response to custodial police questioning, Appellant admitted that, on the previous day, March 29, he sold five bags of heroin to Thomas. A grand jury later indicted Alvarado for heroin distribution resulting in death, in violation of 21 U.S.C. §§ 841(a)(1) and 841(b)(1)(C).

Prior to trial, Appellant filed a motion in limine to exclude evidence of statements made by Thomas, including statements by which Thomas told friends that he bought heroin from a drug dealer named “Fat Boy,” referring to Appellant. The district court deferred resolution of the motion until trial and at that time admitted the statements.

At trial, several pieces of evidence linked Appellant to Thomas, including cell phone records and witness testimony. Also, it was shown that Thomas also used Xanax and Benadryl shortly before his death. Additionally, Virginia’s Assistant Chief Medical Examiner, Dr. Gayle Suzuki (“Suzuki”) testified that Thomas died of “heroin intoxication” and that “without the heroin, [Thomas] doesn’t die.”

The jury retired to deliberation after receiving jury instructions from the district court. Soon thereafter, the jury sent a question to the district judge asking whether the phrase “death resulted from the use of the heroin”—a phrase contained in the jury instructions—meant “solely from the use of the heroin or that the heroin contributed to [Thomas’] death.” In an attempt to prevent the jury from further confusion, counsel for both parties and the district court agreed not to provide any clarifying instructions to the jury. The jury later returned a guilty verdict and Appellant alleges three separate errors on the part of the district court. Each is discussed below.

District Court Did Not Err in Refusing to Clarify Jury Instructions

First, Appellant contended that the district court erred in failing to clarify for the jury the meaning of the “death results from” statutory enhancement element of the offense. The Fourth Circuit pointed out that it reviews the district court’s decision not to give further clarifying instruction for abuse of discretion. Also, when, as in this case, a party fails to object to an instruction or the failure to give an instruction, the Fourth Circuit reviews for “plain error.”

The Fourth Circuit initially pointed out that it was significant that after the court received the jury’s inquiry to clarify “results from,” Appellant’s counsel did not complain that the court’s response was unfair or inaccurate. Additionally, the Fourth Circuit stated that the “results from” language is typical of but-for causation language and the district court properly treated it as such. The Fourth Circuit also stated that but-for causation evidence plagued the record and therefore it could not conclude that the district court committed plain error, or even abused its discretion.

District Court Did Not Err in Refusing to Include Foreseeability of Death Element

Second, Appellant contended that the district court erred in failing to instruct the jury that defendants should only be held liable under this statute for the foreseeable results of their actions. Appellant argued that United States v. Patterson—the controlling law as to this issue—had changed and therefore this issue needed to be resolved once more and in a different manner.

The Fourth Circuit quickly dismissed this alleged error, stating that Patterson remains good law on this issue. Patterson states that the plain language of § 841(b)(1)(C) does not require that, prior to applying the enhanced sentence, the district court find that death resulting from the use of a drug distributed by a defendant was a reasonably foreseeable event. For this reason, the Fourth Circuit concluded that the district court fairly stated the controlling law in refusing to instruct the jury that § 841(b)(1)(C) contains a foreseeability requirement.

District Court Did Not Err in Refusing to Exclude Hearsay Evidence

Finally, Appellant contended that the district court erred in admitting hearsay that Thomas had said that he purchased heroin from “Fat Boy,” a name referring to Appellant. The Fourth Circuit noted that the district court admitted this hearsay under the “statement against interest” exception to hearsay and that exception allows hearsay to be admitted if (1) the declarant is unavailable, (2) the statement is genuinely adverse to the declarant’s penal interest, and (3) corroborating circumstances clearly indicate the trustworthiness of the statement. Appellant only contended prong (2) of this test. Additionally, Appellant contended that his Sixth Amendment Confrontation Clause right was violated.

The Fourth Circuit found that even if there was error in admitting this hearsay evidence under the statement against interest exception, the error was harmless in light of the strength of the other evidence against Appellant. The Fourth Circuit noted that the other evidence all but conclusively confirms that only Appellant sold heroin to Thomas on the day of his death and that Thomas injected that heroin soon thereafter, resulting in his death.

The Fourth Circuit also stated that Appellant’s Confrontation Clause argument was unpersuasive because Thomas’ hearsay statement was not testimonial. This statement was not testimonial because it was made to friends in an informal setting. Because the statement was not testimonial, its admission does not implicate the Confrontation Clause.

Judgment Affirmed

The Fourth Circuit held that the district court did not err in any of the ways Appellant alleged. For this reason, the Fourth Circuit affirmed Appellant’s conviction.

One judge dissented in part, arguing that the jury instructions were not sufficiently clear.