14 Wake Forest L. Rev. Online 47

Nick Tremps

Introduction

Over the past few decades, one particular legal issue has permeated throughout collegiate athletics. At the forefront of every collegiate student-athlete’s mind in recent years is the question: “should I be getting paid for this?” Or, at the very least, should they be receiving more rights and protections other than financial aid and some athletic gear to proudly wear around campus? At first blush, the answer to these questions for all collegiate student-athletes might appear to be yes. Such athletes spend countless hours training, practicing, and competing in their respective sports, all while balancing a full academic schedule and a social life—assuming they are fortunate enough to have any remaining time. Because these universities undeniably receive, at a minimum, nationwide recognition and increased tuition dollars as a result, student-athletes have begun to ask whether compensation or additional protections are warranted. Relevant to this inquiry is the National Labor Relations Act (the “NLRA” or the “Act”), one possible avenue for receiving such compensation or protections. However, this Note argues that the vast majority of collegiate student-athletes should not be able to enjoy the protections afforded by the NLRA.

The recent movement towards classifying student-athletes as “employees” of their respective institutions has its origins in Northwestern University & College Athletes Players Association. In an issue of first impression for the National Labor Relations Board (the “NLRB” or the “Board”), a group of Northwestern University football players sought to unionize under the NLRA, basing their claim under the statutory definition of “employee” in § 152(3) of the Act. While the Regional Director for Region 13 initially concluded that the athletes were employees within the meaning of Section 152(3) of the Act based in part on substantial findings that these athletes bring in significant revenue for the university, the Board ultimately declined to exercise jurisdiction. Thus, the Board left open the question of whether collegiate student-athletes were employees under the Act.

On September 29, 2021, General Counsel Jennifer Abruzzo of the NLRB issued Memorandum GC 21-08, which explains her prosecutorial position that “certain Players at Academic Institutions [are to be] employees under the Act.” Specifically, the memorandum provides that “scholarship football players at private colleges and universities, or other similarly situated Players at Academic Institutions, [should be] employees under the Act.” General Counsel Abruzzo further explained that she may pursue violations of § 158(a)(1) where an institution or employer misclassifies these students as “student-athletes.” Importantly, Memorandum GC 21-08 reinstated NLRB GC Memorandum 17-01, which elaborated on Northwestern University and two other cases that further support the position that student-athletes are “employees” within the meaning of the Act.

Memorandum GC 21-08 sets the stage for student-athletes from a variety of different athletic programs to claim “employee” status under the NLRA. However, the question remains open as to which student-athletes are “similarly situated” to the plaintiffs in Northwestern University.

In Part I, this Note discusses a brief history of the National Collegiate Athletic Association (the “NCAA”) and how the NCAA’s focus, purpose, and oversight have transitioned over time. Part II then discusses the statutory definitions of “employee” under federal law in relation to its applicability to collegiate student-athletes who compete in non-revenue-generating athletic programs at private universities. Specifically, it focuses on the NLRA and the protections that proponents argue should be afforded to these athletes. Part III proceeds by discussing recent developments in case law regarding student-athletes as “employees” under federal statutes, with a particular focus on cases discussing the NLRA. Importantly, Part IV outlines Memorandum 21-08, in which the General Counsel of the NLRB explains that her prosecutorial position moving forward is that collegiate football players at private universities, as well as other similarly situated players, are “employees” within the meaning of the Act. Finally, in Part V and VI, this Note discusses how revenue-generating student-athletes will inevitably be classified as “employees” under the NLRA and concludes that non-revenue-generating student-athletes should not be afforded the same classification because they are not able to satisfy two elements under the common-law test employed by the NLRB: that is, they neither “perform a service” for their respective institutions nor do they receive payment or compensation.

I. Overview of the NCAA

More than a century ago, the Intercollegiate Athletic Association of the United States was formed to address the pervasive injuries and deaths occurring at alarmingly high rates in intercollegiate football games. Prior to President Theodore Roosevelt’s plea to address these issues, schools dealt “with the same issues that we face today: the extreme pressure to win, which is compounded by the commercialization of sport, and the need for regulations and a regulatory body to ensure fairness and safety.” Officially renamed the National Collegiate Athletic Association in 1910 and comprising sixty-two colleges and universities at the time, the Association’s initial mission focused on “regulat[ing] the rules of college sport and protect[ing] young athletes.” The NCAA’s continued, steadfast commitment to amateurism and ensuring the “student” remains in “student-athlete” traces back to the 1940s and the NCAA’s adoption of the “Sanity Code,” which established “principles that covered financial aid, recruitment and academic standards and were intended to ensure amateurism in college sports.”

Today, the NCAA, a member-led organization, has maintained its protectionist view of student-athletes, focusing on “cultivating an environment that emphasizes academics, fairness, and well-being across college sports.” The NCAA’s regulations center around the concept of amateurism, where “the student-athlete is considered an integral part of the student body, thus maintaining a clear line of demarcation between college athletics and professional sports.” Accordingly, from its formation, the NCAA and student-athletes alike have been of the mindset that student-athletes attended universities primarily for educational reasons, and the NCAA was simply an organization formed to protect its student-athletes and to foster a fair and level playing field. However, since President Roosevelt’s seemingly simple request to “clean up the game,” the NCAA’s member schools have come to include 1,098 colleges and universities competing in 102 different athletics conferences. These universities are comprised of “[n]early half a million college athletes [that] make up the 19,886 teams that send more than 57,661 participants to compete each year in the NCAA’s ninety championships in twenty-four sports across three divisions.”

The sheer number of athletes, teams, universities, and conferences has required the NCAA to implement a governance structure managed by full-time professional leadership. The Board of Governors is the NCAA’s highest governing body, primarily made up of presidents and chancellors, along with two independent members who implement policies pertaining to the Association and other central issues. While these policies have an indirect effect on student-athletes, policies that directly affect collegiate student-athletes derive from various legislative bodies or committees that propose rules and regulations with the goal of “upholding and advancing the Association’s core values of fairness, safety and equal opportunity for all student-athletes.” Committee members—volunteers from member colleges and universities—ultimately decide which regulations or policies to adopt and implement. In promulgating and adopting a rule, the NCAA ensures that the proposed rule reflects its time-honored adherence to the educational component of collegiate athletics. For example, the 2022–23 NCAA Division 1 Manual provides that “[i]ntercollegiate athletic programs shall be maintained as an important component of the educational program, and student-athletes shall be an integral part of the student body.” Thus, despite the clear commercialization of modern college sports addressed in this Note, the NCAA nonetheless rightfully continues to ensure that student-athletes remain students first and athletes second.

II. Statutory Definitions of “Employee” and “Employer”

At the outset, it must be recognized that the NLRB “has exercised jurisdiction over private, nonprofit universities for more than [fifty] years” and that the NLRA only covers private employers. As a result, college athletes at public universities, even if deemed to satisfy the “employee” definition, cannot currently organize or enjoy any protections under the NLRA. The stated purpose of the NLRA is to federally manage labor relations by “encouraging the practice and procedure of collective bargaining . . . for the purpose of negotiating the terms and conditions of [workers’] employment or other mutual aid or protection.” The NLRA begins with a lengthy preamble that summarizes the federal government’s reasonable position that strenuous labor relations largely impede interstate commerce. Because of the interstate nature of modern collegiate athletics and the millions of dollars in revenue generated, proponents of student-athletes’ classification as “employees” rely on the NLRA to further their position.

Section 152 of the NLRA defines both “employer” and “employee,” albeit somewhat vaguely. “Employer” is defined in pertinent part as “any person acting as an agent of an employer,” and “employee” is defined as “any employee . . . or any other person who is not an employer” as defined by the Act. While the NLRA definition is not particularly helpful, the NLRB, following Supreme Court precedent, has applied the common-law definition in determining whether an individual qualifies as an “employee” under the NLRA. The common-law definition provides that “an employee is a person who performs services for another under a contract for hire, subject to the others’ control or right of control, and in return for payment.”

Once deemed an employee under the NLRA, an employee may engage in protected § 157 activity without interference from his or her employer. Section 157 provides that “[e]mployees shall have the right to self-organization, to form, join, or assist labor organizations, to bargain collectively through representatives of their own choosing, and to engage in other concerted activities for the purpose of collective bargaining or other mutual aid or protection . . . .” Additionally, § 158(a)(1) protects these rights by prohibiting an employer from interfering with an employee’s § 157 rights in any way. Accordingly, if a particular class of collegiate student-athletes is deemed to be employees of their universities, they may freely engage in protected concerted activity without obstruction or interference from their institutions or the institution’s agents.

While its application is outside the scope of this Note, the Fair Labor Standards Act’s (the “FLSA”) similarly ambiguous definition of “employee” shines light on the difficulty in classifying collegiate student-athletes as “employees” of their universities. The FLSA defines employer to include “any person acting directly or indirectly in the interest of an employer in relation to an employee . . . .” Similar to the ambiguous definition provided by the NLRA, an employee is defined as “any individual employed by an employer.” The FLSA differs, for purposes of this Note, in that it provides guarantees to employees for payment of a federally mandated minimum wage and overtime pay, among other guarantees. In comparison, as mentioned above, the NLRA would protect collegiate student-athletes from employer-interference regarding any collective bargaining activity.

III. Development of Recent Cases in Relation to Student-Athletes’ Employee Status Under Federal Law

A. Northwestern University

The recent development towards student-athletes receiving “employee” status under the NLRA first began with a group of scholarship football players at Northwestern University. In their petition, the players contended that they were “employees” within the meaning of the Act and thus entitled to the protections afforded in §§ 157 and 158 of the Act. In holding that the scholarship football players were “employees” under § 152(3), the Regional Director analyzed various characteristics pertaining to the relationship between the employer (Northwestern University) and its alleged employees (the scholarship football players).

The Regional Director first analyzed the conditions that the players are subject to, such as requiring the freshmen and sophomore players to live in on-campus dormitories, abide by a strict social media policy, adhere to strict alcohol and drug policies, and submit to limitations on the athletes’ clothing. The analysis then turned to the amount of time student-athletes devote to their sport, such as a month-long training camp before the start of the season, daily itineraries, practice schedules, and the twelve games per season that required significant travel time. Finally and most importantly, the Regional Director analyzed the university’s revenue generated from its football team, noting that during the preceding season alone, the football team generated $30.1 million in revenue, which the university used to subsidize its non-revenue-generating sports partially. In concluding that the players were employees of Northwestern University within the meaning of the Act, the Regional Director also determined that “[l]ess quantifiable but also of great benefit to the Employer is the immeasurable positive impact to Northwestern’s reputation a winning football team may have on alumni giving and increase in number of applicants for enrollment at the University.”

Despite this potentially monumental development, the NLRB ultimately declined to exercise jurisdiction regarding the Regional Director’s decision. The Board first explained that the case “raises important issues concerning the scope and application of Section 2(3), as well as whether the Board should assert jurisdiction in the circumstances of this case even if the players in the petitioned-for unit are statutory employees . . . .” However, the Board held that “it would not effectuate the policies of the Act to assert jurisdiction in this case, even if we assume, without deciding, that the grant-in-aid scholarship players are employees within the meaning of Section 2(3).” Thus, while the Board did not reach the merits of the issue because asserting jurisdiction would not promote stability in labor relations, a final judicial determination still lingered regarding whether Northwestern University’s football players were “employees” under the Act.

B. Trustees of Columbia University

While outside the collegiate student-athlete context, the NLRB addressed an issue in Trustees of Columbia University that would serve as an important basis for future NLRB decisions. In Trustees of Columbia University, undergraduate and graduate student-assistants petitioned the Board for classification of “employee” status under § 152(3) of the NLRA. At issue was “whether students who perform services at a university in connection with their studies are statutory employees within the meaning of Section 2(3) of the National Labor Relations Act.”

The Board’s analysis began with the Act’s broad, inclusive language in § 152(3), expressly noting that none of the exceptions apply to students “employed” by their colleges or universities. Similar to Northwestern University, the Board then employed the common-law employment test for an employer-employee relationship, which requires that “the employer have the right to control the employee’s work, and that the work be performed in exchange for compensation.” First, the Board determined that Columbia University exerted significant control over the student assistants in that failure to adequately perform their duties resulted in counseling or removal from the position. Second, the Board found that the student assistants received compensation for their services. Importantly, however, the student-assistants’ compensation was in part a payment the student-assistants received that was distinct from any scholarship and was “not merely financial aid.” The Board noted that the funding provided to the student-assistants was “not akin to any scholarship aid passed through the university” and that “[t]he Board and the courts have repeatedly made clear that the extent of any required ‘economic’ dimension to an employment relationship is the payment of tangible compensation.”

In concluding that the student-assistants were common-law employees and thus entitled to bargain collectively and enjoy the protections of the NLRA, the Board reasoned that “where a university exerts the requisite control over the research assistant’s work, and specific work is performed as a condition of receiving the financial award, a research assistant is properly treated as an employee under the Act.” However, the Board expressly stated that its holding did not require the Board to “find workers to be statutory employees whenever they are common-law employees, but only that the Board may” find them to be statutory employees. Accordingly, the Board’s holding in Trustees of Columbia University sets the basis moving forward that student-athletes might be considered “employees” within the meaning of the Act if they satisfy the common-law definition employed by the NLRB.

C. Berger v. NCAA and Johnson v. NCAA

While the NLRB has applied the common-law definition of “employee” in interpreting § 152(3)’s broad language, it is important to recognize that there is a second test that modern courts have employed in determining whether an individual or particular class of individuals constitutes an “employee.” In Berger v. NCAA, two women who competed on the University of Pennsylvania women’s track and field team sued the university, the NCAA, and more than 120 other Division 1 schools, “alleging that student athletes are ‘employees’ within the meaning of the FLSA.” While the NLRA in pertinent part protects employees from employer-interference when engaging in protected concerted activity, the FLSA provides other protections, such as requiring “every employer to pay ‘his employees’ a minimum wage . . . .”

To determine a collegiate student-athlete’s status as an “employee” under the FLSA, the Seventh Circuit first explained that courts “must examine the ‘economic reality’ of the working relationship between the alleged employee and the alleged employer to decide whether Congress intended the FLSA to apply to that particular relationship.” Under this economic reality test, the court reasoned that “the long tradition of amateurism in college sports, by definition, shows that student athletes . . . participate in their sports for reasons wholly unrelated to immediate compensation.” Thus, the court concluded that this time-honored practice of amateurism outlines the economic reality between universities and their student-athletes, and therefore, the student-athletes could not satisfy this test. In so doing, however, the court failed to correctly analogize student-athletes to students participating in work-study programs, which receive “employee” status under the FLSA. Moreover, the court’s reasoning is somewhat circular: it relied on the amateur status of these athletes and the tradition of amateurism to determine that they were not “employees.”

Contrary to the Seventh Circuit’s holding, one of the most recent cases involving the “employee” status of student-athletes is Johnson v. NCAA. In that case, the plaintiffs—primarily student-athletes from non-revenue-generating sports—alleged in part that their respective schools received significant financial benefits as a result of their participation in collegiate athletics, and therefore, they were entitled to compensation. Applying the economic realities test, the United States District Court for the Eastern District of Pennsylvania analyzed “the economic realities of the relationship in determining employee status under the FLSA” and concluded that the student-athlete plaintiffs could be considered employees. However, this holding simply stated that the student-athlete plaintiffs could be considered employees under the FLSA, meaning the complaint merely survived the defendants’ motion to dismiss. The defendants appealed to the Third Circuit, which agreed to hear an interlocutory appeal “on the question of whether Division 1 student-athletes can be employees of their schools solely by virtue of their participation in interscholastic athletics.” Thus, while Berger and Johnson are instructive in that they demonstrate the emphasis courts place on the economic relationship between student-athletes and their respective institutions, there is no current judicial determination regarding whether student-athletes are employees within the meaning of the FLSA.

IV. General Counsel Jennifer Abruzzo’s Memorandum

On September 29, 2021, Jennifer Abruzzo, General Counsel of the NLRB, issued Memorandum GC 21-08. Memorandum GC 21-08 “provide[d] updated guidance regarding [her] prosecutorial position that certain Players at Academic Institutions are employees under the Act” and reinstated Memorandum GC 17-01, which addressed Northwestern University. General Counsel Abruzzo explained that “certain Players at Academic Institutions are employees under the Act and are entitled to protection from retaliation when exercising their Section 7 rights.” Most notably, the memorandum provided that “although the Board in Northwestern University declined to exercise jurisdiction over scholarship football players at that university, nothing in that decision precludes the finding that scholarship football players at private colleges and universities, or other similarly situated Players at Academic Institutions, are employees under the Act.”

Relying in part on the Board’s previous decisions in Boston Medical Center Corp. and Trustees of Columbia University, Abruzzo concluded that certain collegiate student-athletes “perform services for their colleges and the NCAA, in return for compensation, and subject to [the NCAA’s and the college’s] control.” She also grounded her position in the statutory language of § 152(3) and the underlying policies of the NLRA. As in Trustees of Columbia University, where the Board noted that none of the exceptions applied to work-study students, Abruzzo similarly noted that the football players do not fall under any of the exceptions. In reaching her conclusion, Abruzzo recognized the broad, expansive language of § 152(3) and that the Board has consistently applied common-law agency rules when applying the Act’s broad language.

The memorandum included detailed findings concerning the football players in Northwestern University, reiterating that those players met the common-law test to establish an employer-employee relationship. For example, the universities profited tens of millions of dollars, the players positively impacted the university’s reputation, and increased financial donations from alumni, all while receiving payment and being subject to the university’s strict control. Thus, Abruzzo confidently concluded that the football players were “employees” within the meaning of the Act and undoubtedly satisfied the common-law test. However, the question remains: which class of student-athletes are similarly situated to the football players in Northwestern University?

V. The Common-Law Definition of “Employee”

The NLRB has consistently applied the common-law definition of “employee” in determining whether an individual is an “employee” within the meaning of the Act. In GC Memorandum 21-08, addressed in Part IV, General Counsel Abruzzo explained that “[t]he Board has also applied common-law agency rules governing the employer-employee relationship when applying the Act’s expansive language and purpose to determine employee status.” The common-law definition used by the NLRB is that “an employee is a person who performs services for another under a contract for hire, subject to the others’ control or right of control, and in return for payment.” Notably, the U.S. Supreme Court has supported the NLRB’s use of the common-law definition. For example, in NLRB v. Town & Country Electric, the Court recognized that the language of § 152(3) is broad and noted that the Board’s interpretation of “employee” reflects Congress’ intent. The Court explained that “[i]n the past, when Congress has used the term ‘employee’ without defining it, we have concluded that Congress intended to describe the conventional master-servant relationship as understood by common-law agency doctrine.” Thus, in determining whether “employee” status can extend to a particular group of student-athletes, the NLRB will employ common-law agency rules.

VI. Non-Revenue-Generating Student-Athletes Are Not Employees Within the Meaning of the Act

Because collegiate student-athletes participating in non-revenue-generating sports at private colleges or universities are not similarly situated to the revenue-generating football players in Northwestern University, they should not be entitled to enjoy “employee” classification under the NLRA. Collegiate athletic programs can be bifurcated into two broad categories. The first category, which includes the Northwestern University football players, is revenue-generating sports. For purposes of this Note, revenue-generating sports include Division 1 men’s basketball and football programs. As laid out below, many commentators and legal scholars conclude that these programs undoubtedly provide great financial services for their respective institutions. The second category is non-revenue-generating sports, which includes all other athletic programs, such as track and field, golf, tennis, baseball, soccer, and swimming. While every student-athlete considers his or her sport important, as discussed below, the fact of the matter is that these athletes simply do not “perform services” equivalent to that of their revenue-generating counterparts.

A. Applying the Common-Law Test to Student-Athletes in Non-Revenue-Generating Sports

1. Non-Revenue-Generating Student-Athletes Do Not “Perform Services” for Their Institutions

As discussed above, the NLRB often applies common-law agency rules to determine if an employer-employee relationship exists. The common-law test provides that an employee is one “who perform[s] services for another and [is] subject to the other’s control or right of control” in return for compensation. Under this test, both Abruzzo and the Regional Director in Northwestern University properly concluded that the Northwestern University football players, as revenue-generating student-athletes, could be considered “employees” within the meaning of § 152(3) of the Act.

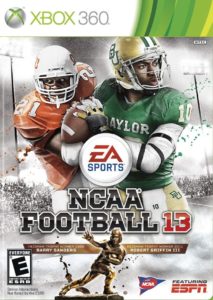

At the Division 1 level, college football and basketball programs generate exorbitant revenue not only for the institutions themselves but also for their respective conference and the NCAA. In all athletic departments of NCAA member schools, “football is the key driver of athletic department operations,” both in terms of revenue and general name recognition. For example, in 2019, the top twenty-five teams in college football generated a combined $1.5 billion in profit for their colleges and universities. At the conference level, the Big Ten Conference recently signed a broadcasting deal with major cable networks and a streaming service that will produce over $7 billion in revenue for the conference for the next seven years. The College Football Playoff, comprised of college football’s top four teams, recently approved a postseason expansion estimated to generate nearly $2 billion a year. Moreover, in 2016, the NCAA signed an eight-year extension with Turner Sports to continue broadcasting coverage of the NCAA basketball tournament, which will produce $8.8 billion for NCAA member schools. Based on these numbers alone, it is clear that the student-athletes participating in Division 1 men’s basketball and football programs unquestionably “perform services” by generating enormous amounts of revenue for their universities or conferences and are thus “similarly situated” to the football players in Northwestern University.

In comparison, student-athletes participating in non-revenue-generating athletic programs do not “perform services” for their institutions. As the author of this Note is a former Division 1 student-athlete in a traditional non-revenue-generating sport, in no way is this Note attempting to devalue these programs. However, these sports do not produce the same tangible returns for private institutions as men’s basketball and football programs. As previously discussed, in analyzing whether student-athletes “perform services” for their colleges or universities, courts emphasize the financial component of the relationship—specifically, the revenue generated from that sport. Using revenue as the guiding metric, this Note highlights that non-revenue-generating sports, as a whole, simply do not generate the “cold, hard cash” that sports like football and basketball produce.

Take the University of Notre Dame and Duke University as paradigmatic. In 2021, Notre Dame reported a combined revenue from men’s basketball and football of $91,563,855, offset by $48,630,144 in expenses, resulting in a net profit of $42,933,711. In all other sports, the revenue generated amassed to a mere $4,436,705 while accruing $33,132,089 in expenses, resulting in a net loss of $28,695,384. Similarly, Duke University reported a combined men’s basketball and football revenue of $59,860,751, expenses of $36,756,084, and a net profit of $23,104,667. Non-revenue-generating sports, on the other hand, generated $27,774,939 in revenue, $34,157,042 in expenses, and a net loss of $6,382,103.

These consistent, year-over-year losses from non-revenue-generating sports result in only 2.26 percent of NCAA member schools generating a profit from their athletic departments. To combat the sizable financial losses of non-revenue-generating sports, these institutions are commonly forced to subsidize them through the profits realized from revenue-generating sports. Because of the expenses accrued, profits from an institution’s men’s basketball and football programs are “diverted to cover the expenses of non-revenue programs,” and those profits are “often dissipated in helping to keep other programs operating.” It is for this additional reason that revenue-generating sports are “performing a service” for their institutions. While proponents argue that non-revenue-generating sports nonetheless “perform a service” by graduating at higher rates or promoting the university’s name in niche markets, this is simply not enough to meet the requisite standards for an employer-employee relationship. Even in other contexts, the NLRB and U.S. Supreme Court have concluded that the Act covers an employee when the employer-employee relationship is an “economic relationship.” That is, the employer must experience a direct financial benefit, and the employee must receive tangible compensation. Because non-revenue-generating sports are essentially performing a financial or economic disservice to their institutions, they accordingly do not meet this component of the common-law test.

2. Non-Revenue-Generating Student-Athletes Are Subject to Their Institution’s Control or Right of Control

The common-law test for establishing an employer-employee relationship requires that the employee be “subject to the other’s control or right of control.” In applying the test, the U.S. Supreme Court has considered whether the employer has the right to control the manner and means of the employee’s production. As this author witnessed and experienced firsthand, the NCAA and its member institutions undoubtedly exert substantial control over all its student-athletes. Thus, while unable to satisfy the other two components of the test, student-athletes in non-revenue-generating sports are certainly controlled by or subject to the control of their respective institutions. While this Note does not expound upon the control wielded over student-athletes in revenue-generating sports, Abruzzo’s memorandum, for example, depicts the level of control Northwestern University and the NCAA had over members of the football team.

For the majority of student-athletes in non-revenue-generating sports, the reality of intercollegiate athletics is that they typically spend more time training, practicing, and competing than they spend time in the classroom or studying. At the NCAA level, the NCAA places copious restrictions on all of its Division 1 member institutions, such as academic eligibility requirements, regulations and restrictions pertaining to each individual sport, and numerous restrictions that further the NCAA’s amateurism principles. Further, NCAA regulations also expressly state that a student-athlete’s financial aid may be reduced or canceled if the student-athlete commits any of the acts expressly provided in § 15.3.5 of the Division 1 Manual.

The NCAA directs that it is the responsibility of each member institution to conduct and control its athletic department in a manner that ensures compliance with the NCAA’s Constitution and bylaws. At the institutional or conference level, additional or supplemental regulations may also be placed on student-athletes. For instance, Stanford University’s Student-Athlete Handbook provides that “[e]very student-athlete is subject to NCAA, Pac-12, and Stanford University rules and regulations that can affect [their] collegiate eligibility.” Additionally, the Athletic Policy Manual of Duke University provides that its Drug Testing Program is separate from the NCAA’s and that “the University may test for any substance … not contained on the NCAA’s list of banned substances . . . .” Failure to comply with applicable institutional-level regulations may result in a reduction, cancellation, or nonrenewal of a student-athlete’s financial aid.

Lastly, all student-athletes, including members of non-revenue-generating athletic programs, are subject to their respective team’s rules and regulations. Individual team rules and regulations have been a long-standing tradition in intercollegiate athletics. While team rules in both revenue and non-revenue-generating sports were initially meant to implement goals or minor procedures for the upcoming season, these regulations have transformed into a system that “invades, inspects, lords over, stereotypes, discriminates and pronounces judgment on multiple aspects of players’ personal lives.”

For example, at the University of Virginia, one rule orally imposed on golf team members, including this author, provided for removal from the morning workout if any team members wore another university’s article of clothing. Surprisingly, in the Texas Tech softball program and Kansas women’s basketball program, team policies also govern relationships and displays of affection. Similar to failing to comply with NCAA regulations, a student-athlete’s financial aid may be reduced or even canceled if the student-athlete violates a team rule. Although this conclusion is certainly not dispositive, student-athletes competing in both revenue and non-revenue-generating athletic programs are certainly subject to the control of their respective institutions.

3. Non-Revenue-Generating Student-Athletes Do Not Perform Services in Return for Compensation

Lastly, where “employee” status under the NLRA certainly fails for non-revenue-generating student-athletes, the common-law test mandates that the employee perform services for another in return for compensation. In 2015, after gaining legislative autonomy, the Power Five Conferences (the Atlantic Coast Conference, Southeastern Conference, Big 12 Conference, Big Ten Conference, and Pac-12 Conference) promulgated legislation that sought to expand statutory financial benefits to all scholarship student-athletes in the conferences. Included in this legislation, and ultimately incorporated into the modern NCAA Division 1 Manual, was a provision permitting the expansion of institutional financial aid to cover “any other financial aid up to the [true] cost of attendance.” This includes “the total cost of tuition and fees, room and board, books and supplies, transportation, and other expenses related to attendance at the institution.” While only initially applicable to the member institutions of the Power Five Conferences, institutions in other conferences have followed suit.

Despite certain conferences expanding the amount of institutional financial aid to cover the true cost of attendance, the NCAA—holding true to its amateurism principles—still mandates that “an individual loses amateur status and thus shall not be eligible for intercollegiate competition in a particular sport if the individual . . . [u]ses athletic skills (directly or indirectly) for pay in any form in that sport,” or engages in similar conduct prohibited in that section. Thus, a student-athlete is still prohibited from receiving compensation from his or her institution outside of institutional financial aid or the minimum amount of stipends used to cover some costs associated with attending the institution.

Many scholars and commenters posit that a student-athlete’s scholarship constitutes compensation, arguing that “college players are already getting paid . . . in the form of free tuition and other benefits.” However, this argument misses the mark. As one analogy aptly provides, contending that a student-athlete’s scholarship constitutes compensation is akin to arguing that a worker is not entitled to a salary because he or she receives insurance. Moreover, the non-revenue-generating student-athlete’s financial aid differs substantially from that of employees in the general employment context. For instance, while employees in other settings are permitted to negotiate certain benefits, NCAA guidelines preclude any such negotiation on the part of the student-athlete. These restrictions are enacted in part to preserve student-athletes’ amateur status by preventing them from receiving true compensation—or “pay,” to use the NCAA’s language—outside his or her institution’s financial aid.

Importantly, any financial aid granted to a student-athlete in a non-revenue-generating program differs from the student-assistants’ compensation in Trustees of Columbia University. In that case, the NLRB concluded that the student-assistants’ services provided to the institution and its faculty resulted in “tangible compensation” or direct payments, and that this exchange constituted “compensation” under the common-law test for an agency relationship. A scholarship is not “tangible compensation” in that the student-athlete is not free to spend it however he or she sees fit. In Trustees of Columbia University, the Board only considered the direct payments the student-assistants received, noting that they were distinct from scholarship aid. Thus, because the NCAA prohibits compensation outside of institutional financial aid or stipends, and apart from any NIL payments that are outside the scope of this Note, non-revenue-generating student-athletes do not receive compensation from their institution and are unable to satisfy this element of the common-law test.

B. Non-Revenue-Generating Student-Athletes Also Fail to Satisfy the Statutory Definition Test

Both the NLRB and the Supreme Court have recognized § 152(3)’s exceptionally broad definition of “employee.” Coupled with the definition’s breadth and the underlying policies of the NLRA, the NLRB is also entitled to significant deference in its statutory interpretation. Further, the NLRB has determined that the absence of a particular group in the statute’s categorial exceptions is strong evidence of coverage. Proponents of student-athletes’ “employee” classification, including Jennifer Abruzzo, therefore cite the absence of collegiate student-athletes in the categorial exceptions as strong evidence of classification. Despite the NLRB’s deference and the presumption for statutory coverage, the NLRB has made clear that statutory coverage may not be extended if “there are strong reasons not to do so.” In this particular context, there are several reasons not to do so.

Because private institutions constitute a small percentage of Division 1 schools, there are severe practical implications if non-revenue-generating student-athletes at private schools are permitted to enjoy the protections of the NLRA, such as collective bargaining. For example, if such a program at a private institution is deemed a bargaining unit, the NLRB would in effect create a convoluted intercollegiate environment where only a small percentage of student-athletes are protected under the Act. Notably, the Board in Northwestern University similarly declined to exercise jurisdiction because the “vast majority” of collegiate athletic programs are operated by state-run institutions. Additionally, distinct from the student-assistants in Trustees of Columbia University, each institution’s teams would determine if an individual team classified a bargaining unit or whether all student-athletes would constitute one bargaining unit. Thus, one private institution may have one bargaining unit per team, and another may have one bargaining unit for its entire athletic program, which could lead to a wide array of discrepancies between the institutions. Lastly, and most significantly, granting “employee” status to non-revenue-generating student-athletes indubitably crosses the line of demarcation between professional and intercollegiate sports. As the Board in Northwestern University explained, while all players for professional sports teams may be represented for purposes of collective bargaining, granting “employee” status to some student-athletes will ultimately leave others completely unrepresented or outside the Board’s jurisdiction. Moreover, the Board’s analysis in that case is applicable here, where enforcement of NCAA regulations and inclusion of additional regulations are left primarily to the individual institutions or the institutions’ respective conferences. Accordingly, there are strong policy reasons not to extend “employee” classification to non-revenue-generating student-athletes.

Conclusion

In the past decade, numerous court decisions, proposed legislation, and General Counsel Jennifer Abruzzo’s Memorandum all point to the inevitable conclusion that student-athletes participating in revenue-generating athletic programs will be classified as “employees” under the NLRA, and perhaps rightfully so. Thus, these athletes will be entitled to the protections afforded under §§ 157 and 158. However, the question remains as to how student-athletes in non-revenue-generating athletic programs will be classified under the NLRA. In employing the common-law test for an employer-employee relationship applied by the NLRB, these student-athletes should not be classified as “employees” of their respective institutions. While their revenue-generating counterparts undoubtedly perform a service for their college or university, the expenses imposed by non-revenue-generating sports on their institutions suggest that these programs do not meet this component of the common-law test. Despite being subjected to significant control of their university, this is not enough in the eyes of the courts and the NLRB to simply classify these student-athletes as employees. Further, the mere fact that many non-revenue-generating student-athletes receive institutional financial aid does not warrant a conclusion that they receive “compensation.” While non-revenue-generating athletic programs are unquestionably important to the landscape of intercollegiate athletics, they are not “similarly situated” to the Northwestern University football players and are thus not entitled to employee-status under the NLRA.